Conquistadors in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia

An installment in our Appalachian History and Culture series

The Euro-centric history I learned in school in the 1960s was woefully inadequate. I suppose that’s the best they could do. After all, the world is a big place with lots going on. There was only enough time to cover the Big Picture. That’s why I was shocked to learn, only a few years ago, of Spanish Conquistadors in the Blue Ridge Mountains.

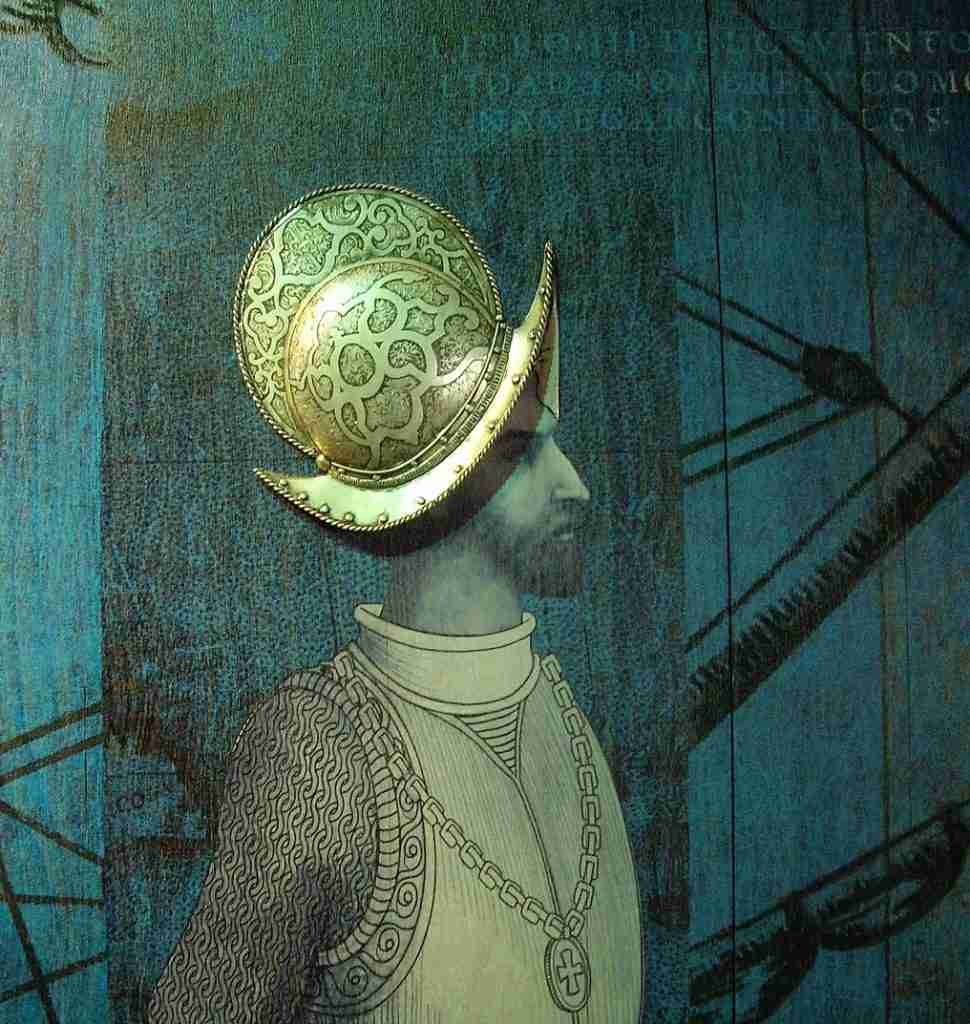

I had learned about Conquistadors and the Age of Discovery in history classes. Names like Pizarro, deSoto, and Cortes were familiar. I could visualize their heavy steel breastplates and helmets with the comb on top and sweeping, pointed sides. I learned of their conquests in Florida, Mexico, and South America. But why were they in Southwest Virginia?

Of course, they were there looking for gold and silver. The Spanish weren’t interested in colonizing; they were there to enrich King Charles. When rumors of “white gold” in the Western mountains reached the Spanish fort in Santa Elena (now Parris Island, SC), Juan Pardo led about 100 men through the mountains of Western North Carolina into Southwest Virginia. But they didn’t find gold or silver.

The ”White Gold” Was Salt

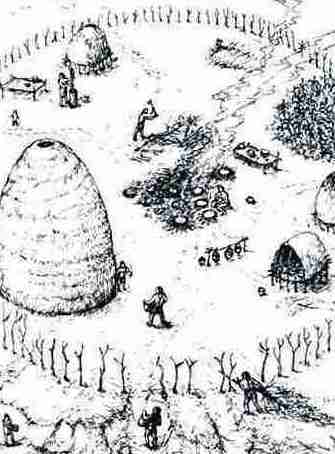

Pardo discovered a Yuchi village, historically known as Maniatique (now Saltville, VA), on the banks of the North Fork of the Holston River. The Yuchi were Woodland Indians who lived in wigwams (dome-shaped, wood-framed houses). For the era, they had an advanced economy: they were hunter-gatherers who practiced agriculture and mining and traded with other tribes. The Yuchi’s wealth was salt.

There were salt pits everywhere. Eons ago, the area was an ocean floor. Over time, the land shifted, and seawater evaporated, leaving salt deposits and other minerals behind. Groundwater passing through these sediments brought salt to the surface in liquid form as brine springs or seeps. The brine was collected and boiled. When the brine evaporated, salts were re-crystallized and left behind. Salt was the Yuchi’s cash crop. Business was steady: the Holston’s North Fork flowed through mountain gaps, and Maniatique became a crossroads for animals and people seeking life-giving salt. The Museum of the Middle Appalachians in Saltville, VA, displays artifacts and fossils from the salt pits, including Wooly Mammoth and Yuchi artifacts.

When the Spaniards arrived, they demanded food, supplies, and information regarding the “white gold.” The Yuchi refused them on all counts. The Conquistadors retreated to their fort at Joara (near Morganton, NC) and regrouped for an attack on Maniatique. Details about the attack aren’t available, but archaeological and historical records infer that the Yuchi village was destroyed and that survivors were taken in by the surrounding Creek Nations. In the 19th Century, the Creeks were driven from their lands and resettled in Oklahoma in a process known as the Trail of Tears.

One historical record notes that a Yuchi woman named Luisa Mendez, who was kidnapped from Maniatique, married a Spanish soldier named Juan de Ribas. The two eventually left the interior when the Spanish abandoned the Carolinas, and by 1600, they were in St. Augustine, Florida.

The Legacy of the Yuchi and the Spanish Conquistadors

The Pardo expedition, though little-known, left an indelible mark on the region. It was a tale of first contacts, cultural exchanges and misunderstandings, and ambition clashing with the reality of the New World. The Spanish outposts established during this expedition were among the earliest European settlements in the interior of North America, predating the English colonies by several decades.

The interaction between the Spanish and the Yuchi is a poignant reminder of the complexities of history. The displacement of indigenous populations and the consequences of colonization are themes that still resonate. Yet, the story of the Pardo expedition also speaks to the human lust for conquest and power.

More Appalachian History & Culture

Find more stories from the region’s past on the History and Culture page.

Appalachian History and Culture Collection

Enjoying Blue Ridge Tales? I hope so. If you’d like to help keep the site ad-free and the stories rolling, you can buy me a coffee.

To stay connected, subscribe to my Blue Ridge Tales newsletter, and have stories and updates delivered once a month to your inbox.