What We Miss When We Talk About Appalachian Stereotypes

An installment in our Appalachian History and Culture series.

Scroll through enough social posts, and you’ll see the same Appalachian stereotypes repeated: Poor. Backward. Uneducated. Stuck. The wording shifts, but the judgment stays the same. It’s often delivered with confidence and very little curiosity.

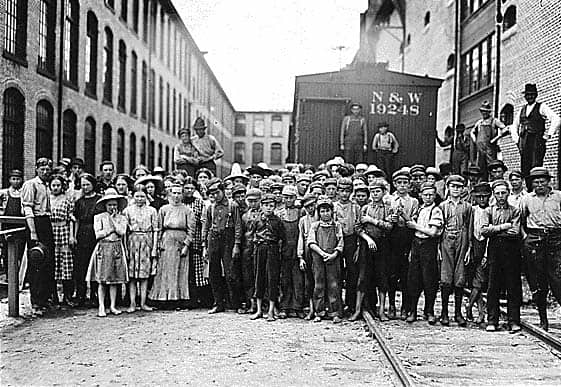

Yes, hardship was real. Poverty was real. Options were limited. Work was hard, repetitive, and sometimes dangerous. Some of my forebears were Appalachian mill workers. Others were farmers and tradesmen. I’m not denying any of the characterizations.

I’m writing because the familiar story is incomplete. It tells you what people lacked, but rarely what they did to make life work anyway. If you only look at what wasn’t there, you miss the competence that had to fill the gap.

Hardship and the Appalachian stereotypes it feeds

Many families lived close to the edge. Education could be limited by distance, money, or the fact that work came first. Medical care could be far away. A steady job wasn’t guaranteed. When work did come, it could wear a body down.

That’s the baseline. Any honest account of Appalachia has to start there.

But baseline conditions don’t explain how folks lived inside the limitations. To understand that, you must look at what daily life required and how people met those requirements.

What competence looked like in everyday life

Work in Appalachia often didn’t come in the form of a single stable role you could build a life around. Many folks stacked forms of labor. A mill job might cover most needs. Other work filled the gaps. A garden mattered. Animal husbandry mattered. Food storage was essential. So was firewood. Helping a neighbor was important because you might need some help later.

This wasn’t variety for its own sake. It was a practical response to uncertainty. If one source of income failed, another had to step in. Being able to shift between kinds of work wasn’t optional. It was how households stayed upright.

Skills were learned the same way. Knowledge didn’t always come through formal training. It came through watching, copying, and repeating until a task could be done automatically. If a machine quit, you learned what it took to get it running again. If a stove smoked, you learned how to fix the draft. If weather threatened a crop, you knew what to do differently next time.

There weren’t diplomas for this kind of learning. The test was whether the task got done.

Repair wasn’t a virtue lesson. It was a necessity. Tools were kept working. Clothes were patched until they couldn’t be patched anymore. Equipment was maintained because replacement might not be possible, or it might wipe out a month’s margin. You didn’t replace what could still be fixed, even if fixing it took time.

Time itself was approached differently. Life followed seasons more than clocks. Folks planned around weather, daylight, planting, and heating. That kind of planning required attention and memory. Small mistakes could turn into serious problems.

None of this looks impressive in a quick snapshot. It doesn’t show up as polished speech or formal credentials. But it’s real competence, built through repetition and necessity, practiced so often it became routine.

Why Appalachian stereotypes miss this

Life today is structured to reduce uncertainty. Education is designed to lead to jobs. Jobs are expected to provide steady paychecks. Services and infrastructure are meant to catch failures before they turn into crises.

In that world, competence often means knowing how to move through systems. You apply. You qualify. You schedule. You rely on predictable rules.

In earlier Appalachian communities, those systems could be thin, distant, or nonexistent. When there’s no dependable fallback, you don’t spend much time comparing options. You figure out what works and keep moving. Skills aren’t chosen because they fit a long-term plan. They’re learned because something needs doing, and there may not be anyone else to do it.

This is where many misunderstandings begin. People look back and focus on what the system didn’t provide. That’s fair. But if you stop there and form your opinion around the common Appalachian stereotypes, you miss what families had to provide for themselves.

A family context, not an exception

My family’s mill-worker history fits this pattern. Mill work could offer steadier wages than some alternatives, but it didn’t fill the gaps left by limited access to education, medical care, and other basic services. It didn’t make food or medicine appear. It didn’t prevent a hard winter. It didn’t remove the need for side work when money got tight.

The competence that mattered most wasn’t about status. It was about function. Keep the household running. Keep the bills handled. Keep the next week from falling apart.

Folks didn’t describe this as courage or determination. They described it as work. They did it because it was necessary.

That story is familiar across Appalachia, even if it rarely gets told in full.

Why Appalachian stereotypes stay in place

The idea of Appalachia as poor and ignorant is an Appalachian stereotype, and it persists because it’s easy to repeat and doesn’t require much thought. It lets outsiders feel superior. If the problem is personal failure, there’s no need to look any further.

That version of the story lines up with what many people can see from a distance. Old houses. Worn clothes. Hard jobs. Fewer institutions. Those things are real, but they aren’t the whole picture.

When scarcity becomes the only lens, flawed conclusions follow. In that world, ambition often looked different. Working constantly just to stay upright left little room for the kind of long-term planning modern systems reward. Informal knowledge gets mistaken for a lack of intelligence. Quiet, local work gets mistaken for passivity.

Those conclusions don’t hold up if you pay attention to what daily life demanded and how folks met those demands.

What a fuller picture allows us to see

When Appalachia is framed only as a cautionary tale, you lose the ability to understand it as a place where people made choices under pressure and developed habits that worked. You also lose a useful lesson for the present. Many of the skills that kept households steady under scarcity are the same skills people rely on when modern systems fail or fall short.

A more accurate view doesn’t require romanticizing anything. It requires looking at the full frame. Hardship was real. So was capability.

If you’re going to talk about Appalachia, you have to talk about both. Because if you only tell the story of what folks didn’t have, you’ll never understand what they managed to build with what they had.

More Appalachian History & Culture

Find more stories from the region’s past on the History and Culture page.

Appalachian History and Culture Collection

Enjoying Blue Ridge Tales? I hope so. If you’d like to help keep the site ad-free and the stories rolling, you can buy me a coffee.

To stay connected, subscribe to my Blue Ridge Tales newsletter, and have stories and updates delivered once a month to your inbox.