Blue Ridge Parkway: The Stories Behind the View

An installment in our Blue Ridge Travel series.

The View That Cost Everything

Drive the Blue Ridge Parkway on a quiet weekday morning, and it’s easy to believe it has always been this way: peaceful and polished. Each curve feels natural, as if the road simply followed the shape the mountains already offered. Beauty like this sometimes comes at a cost.

Beneath the overlooks and picnic tables lies a record of hard choices. Families were uprooted. Ridges were cut. Communities were divided by a project aimed at reviving the economy and showcasing the landscape. The Parkway became one of America’s favorite drives. It also became a monument to what disappeared when it came through.

One such example is the 1930s, when survey crews marked the route through Rock Castle Gorge in Patrick County, Virginia. Families there had built a life in the steep hollows. Orchards, smokehouses, and stone chimneys dotted the slopes. Letters followed. The state condemned the land for what would become the Rocky Knob Recreation Area, part of the new scenic road. Some families accepted the small checks. Others held on until the sheriff left them no choice but to surrender. They were not trespassers. They were owners who believed a deed still carried weight.

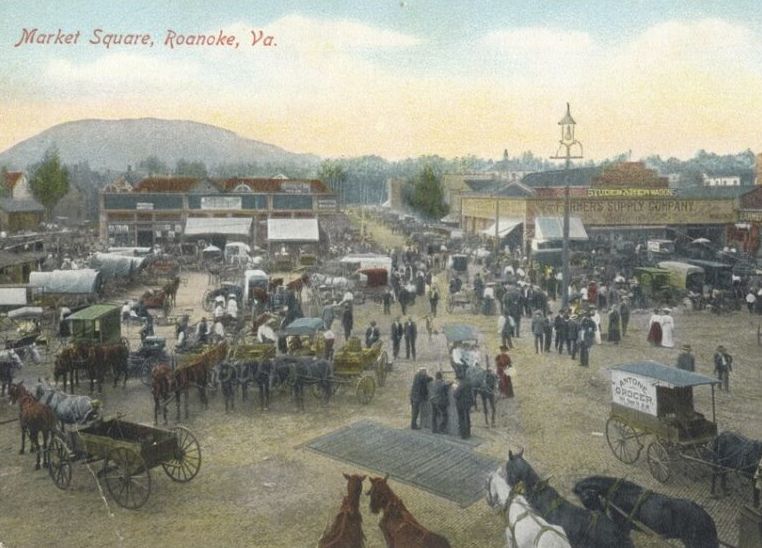

Old-timers talk about the wagons that hauled the last loads up the mountain. One man carried the boards from his cabin to rebuild on cheaper ground a few miles away. Another left his apple trees with the fruit still hanging. Years later, visitors stopped at the overlook and praised the view without realizing they were looking down on what had once been a village. To officials, it was progress. To the families who left, it was the loss of home.

Displacement wasn’t unique to one hollow. It happened along the route through Virginia and North Carolina. The federal plan brought jobs and the promise of tourism, but it also brought new rules for landowners and a hard lesson in how national projects are built. The story of the Blue Ridge Parkway begins here, with the price of a view.

The Builders and the Bargain

The Blue Ridge Parkway was more than just a public works project. It tested whether big government programs could lift people and land at the same time. In 1933, President Franklin Roosevelt visited the newly built Skyline Drive in Virginia. A motor road linking the two new eastern parks looked like a practical way to create jobs and rebuild confidence. Planning began soon after that visit. Construction started near Cumberland Knob on September 11, 1935.

The route choice sparked a political fight. Some wanted the road to swing west into Tennessee from Linville, North Carolina. Others wanted it to continue through North Carolina. Josephus Daniels, a North Carolina power broker and Roosevelt ally, pressed for the North Carolina route. Congressman Robert L. Doughton became the road’s most effective advocate in Washington. He chaired the House Ways and Means Committee and had the leverage to help New Deal legislation that mattered to the White House. The pathe of the Blue Ridge Parkway and the momentum behind Social Security moved through the same rooms, where regional needs and national policy were bargained side by side.

On the ground, crews from the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) cleared slopes, planted trees, and set stone by hand. Many were teenagers who had left farms and mill towns with little more than a bedroll. The CCC sent part of their wages home; the rest bought boots, cards, or a shave at the barber shop. Workers from the Works Progress Administration and the Emergency Relief Administration joined them. During the war years, conscientious objectors in the Civilian Public Service program kept certain landscape projects moving.

Days started before sunrise with coffee in canvas mess tents or clapboard barracks and ended after dark. Tunnels were blasted. Drainage was laid. Slope cuts were shaped to hold. At night, cards slapped against rough wood tables and songs carried across the camps. When the work ended, their projects remained: stone bridges, guard walls, and drains that serve the road as reliably as the day they were built. Visitors see that craftsmanship in every stone guardrail and dry-laid wall.

The bargain was clear: The road brought paychecks to men who needed them and new business to mountain towns. It also cut through family fields and turned once quiet hollows into public ground. For every new overlook, someone lost a view of his own.

A Road Shaped to the Land

From behind the wheel, the Blue Ridge Parkway seems effortless. Building it was not. Stanley Abbott, the young landscape architect who led the design, set out a principle that guided the entire project: fit the Parkway into the mountains so it appears to belong. The road should bend, hide, and reveal in a way that feels natural.

That philosophy shaped every detail. Native plantings frame long views. Stone and timber match what was already here. Billboards and commercial clutter were banned. In places, agricultural easements allowed pastures, split-rail fences, and livestock to remain part of the scene so that the landscape still felt lived-in, not staged. The result is a road that unfolds in sections—a creek, a pasture, a stand of hardwoods, then a sudden view.

Engineering followed the same idea. Twenty-six tunnels cut through rock where switchbacks would have scarred hillsides. Bridges carry the route over rough ground and rivers. The last major challenge awaited at Grandfather Mountain, where the need to protect a fragile slope led to the Linn Cove Viaduct. Built segment by segment from above, it was the final link and a model of care and precision.

The National Park Service continues to manage the road with that balance in mind. It protects views and habitat while keeping the landscape legible to those who live near it and those who come to see it.

The Towns the Parkway Touched

When the cut crews and graders moved through, some towns faded. Others adapted. The Parkway didn’t create change in the mountains, but it made it arrive faster and easier to see. Popular destinations Fries and Galax lie just off the Parkway; Galax is about seven miles from the nearest exit, and Fries another eight beyond, while Meadows of Dan sits right on the route itself.

Meadows of Dan offers a unique story at the Mayberry Trading Post. The store dates to the late nineteenth century and has continued through wars, the Depression, and the arrival of the Blue Ridge Parkway. It once sold flour, bolts of cloth, nails, and news. When the Parkway arrived, it stocked what travelers wanted. People still stop for a look inside a building that has served a ridge community longer than any highway has existed. The television echo in the word Mayberry makes visitors smile, but the real place tells a more complex story. Families there learned how to hold on to something local while the world came to their porch.

Down the ridge, Galax found its footing in music. The Old Fiddlers’ Convention drew players and listeners who valued tunes the way other towns value trophies. A road built for views carried a sound that was already here out into the world. Today, the Blue Ridge Music Center at Milepost 213 makes that tradition easy to find. Summer breezeway sets and amphitheater shows give travelers a chance to hear what local families have played on porches for generations.

In Fries, Virginia, the old textile mill that once ran the town closed, and the New River Trail took root along the rail bed. The mill town learned to welcome hikers and cyclists instead of factory shifts. The hum of looms gave way to the steady spin of bicycle tires and the push of paddles. It didn’t turn Fries into something new; it gave people another reason to cross the New River bridge and stay a while.

These towns don’t tell a single tale. They show how places bend without breaking when the world shifts around them. The road brought tourists and, with them, new ways to make a living.

Culture on the Ridge

Before there were visitor centers, the Parkway’s soundtrack came from local life. On weekends at Mabry Mill, visitors heard conversation, fiddle tunes, and the steady creak of the waterwheel. In Floyd County, general stores served as waypoints where a tune might follow talk about hay or repairs. In Galax, the Rex Theater’s Saturday broadcasts kept old-time sound alive for both locals and travelers.

Later, institutions emerged that made the culture easier for visitors to discover. The Blue Ridge Music Center between Galax and Sparta anchors a network of venues, festivals, and informal gatherings. South of Asheville, the Folk Art Center of the Southern Highland Craft Guild shows how handmade work stayed part of mountain life even as small farms dwindled. The link between CCC craftsmanship and Parkway stonework is clear in the joinery and finishing that still define the road.

Culture here is more than a museum display; it’s part of daily life, carried forward by habit and need.

Stories That Travel the Road

People travel the Parkway for the scenery, but what they often remember are the stories tied to the land. Some are printed on markers. Others are told across kitchen tables. Some are rooted in the land itself.

The Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians negotiated for years over the right-of-way through the Qualla Boundary. The final agreement included payment for tribal land and a state commitment to improve access to the Soco Valley. Cherokee leaders later took part in dedication ceremonies when the road opened through their country. That sequence matters. It shows how communities insisted on terms that recognized their stake in the land and their future on it.

The Brown Mountain Lights near Linville have been part of mountain lore for over a century. Federal investigators attributed the lights to natural and human causes, including train headlamps, car lights, and atmospheric conditions. The legend held anyway. What matters isn’t proof; it’s how the landscape keeps memory and gives people a way to talk about what they feel when the light fades.

Memory also has brick and stone. Across the Shenandoah region, the Blue Ridge Heritage Project has built chimney monuments that carry the names of families displaced when land was taken for park creation. Those sites do quiet work. They remind people that places now seen as pristine were once home to others who had to leave. The same is true along parts of the Parkway line. Loving the view doesn’t erase the cost.

The Blue Ridge Parkway and Its Legacy

Eighty years after the first crews broke ground, the Blue Ridge Parkway keeps doing steady work. It links towns that once stood apart. It keeps views open and farms present in the scene. It slows travel just enough for people to see what remains.

Descendants visit overlooks that carry family names. Rangers hear those stories more often than visitors might guess. Someone will point to a fold in the ridge and say a house once stood there. A relative will name a creek where cattle watered. Moments like that connect public land to private memory.

Design still guides daily choices. The National Park Service maintains the road as both a natural and cultural landscape. The aim isn’t to freeze anything in time but to keep the essentials visible and healthy. That’s why the pace is slow, commercial traffic is banned, and closures follow storms or slides. The road serves as both a highway and a park.

Stanley Abbott said the Parkway should fit the mountains as if nature had put it there. That idea still holds. Stand at an overlook with the wind moving through the trees, and you see what he meant. The engineering fades. What remains is the landscape it was built to protect.

More Blue Ridge Travel

Find more travel stories, routes, and small-town stops on the Blue Ridge Travel page.

View the Blue Ridge Travel Collection here

Enjoying Blue Ridge Tales? I hope so. If you’d like to help keep the site ad-free and the stories rolling, you can buy me a coffee.

To stay connected, subscribe to my Blue Ridge Tales newsletter, and have stories and updates delivered once a month to your inbox.