Inside the World of the Appalachian Song Catchers

An installment in our Appalachian History and Culture series.

The phrase “catching a song” once had a literal meaning in the Southern Appalachians. A singer shared a tune, someone else listened closely, and the melody passed from one memory to another. Nothing was written down. The old songs stayed alive only as long as someone could remember them. When early visitors stepped into the mountains during the twentieth century and began writing those songs on paper or capturing them on portable disc-cutting machines, their work carried consequences they couldn’t have anticipated. These were the Appalachian song catchers, men and women who preserved a tradition at the moment it might have slipped away.

The First Encounters of the Appalachian Song Catchers

The work began quietly. Around 1908, Olive Dame Campbell traveled through the mountains of Kentucky and North Carolina with her husband, a rural educator. She kept notebooks filled with local ballads that reminded her of British songs she had studied earlier in life. Her notes caught the attention of Cecil Sharp, already well known in Britain for his interest in traditional music. He crossed the Atlantic in 1916 to continue what Campbell had started.

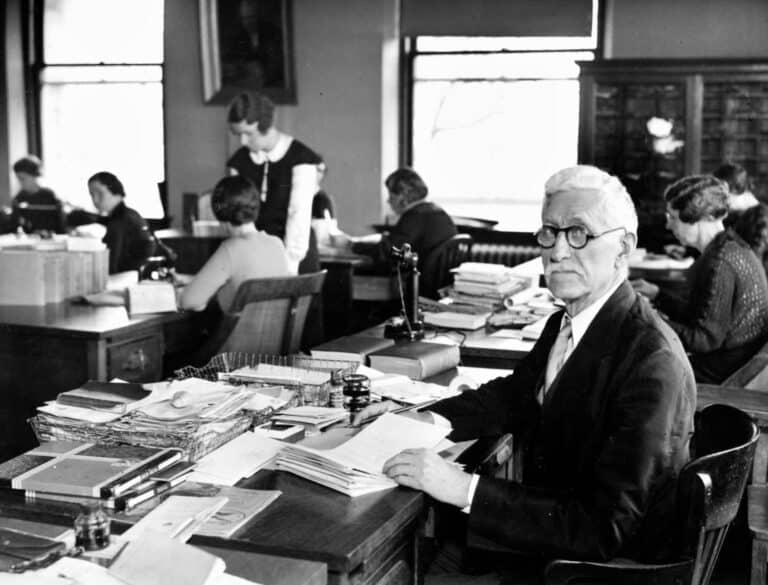

Sharp enlisted the help of Maud Karpeles, an experienced musician who could move quickly between households, build trust with singers, and take down lyrics while Sharp handled the melodies. Together they visited farms, schoolhouses, and family gatherings, working with nothing more than pencil, paper, and a good ear. They aimed to trace old-world ballads that had survived in the hills, sometimes in versions that had vanished in Britain.

What the Appalachian Song Catchers Found

Sharp and Karpeles discovered a repertoire far broader than they expected. They documented ballads that had traveled from the British Isles centuries earlier and found children’s songs, love laments, hymn variants, and fiddle pieces that showed how deeply music was woven into daily life. Local singers carried hundreds of tunes in their heads. Many could not read or write music, but they could remember entire ballads from start to finish without hesitation.

Their focus came with limits. They favored songs with European roots and paid less attention to African American, Indigenous, and locally developed styles. Even so, the manuscripts they produced remain essential records of a tradition that might otherwise be lost. Names of singers appear throughout their notes: families in Madison County, North Carolina, ballad singers in Wise County, Virginia, and households scattered through the Cumberland region.

How Appalachian Song Catchers Did Their Work

Writing down a tune required patience on both sides of the table. A singer might repeat a line several times so Sharp could find the exact rise and fall of the melody. Karpeles often wrote the words while Sharp listened for details of timing and pitch. Travel was slow. Many communities sat miles off the main roads, and introductions came through teachers, ministers, or families who trusted outsiders enough to let them listen.

In these hills, memory served as the archive. Songs shifted slightly from one singer to the next, but the structure held. The collectors’ purpose was simple: catch the tune before it disappeared.

A New Tool in the Mountains

More than twenty years later, another form of song catching reached the region. John and Alan Lomax traveled the country with portable disc recorders that could capture a tune exactly as it was played. Their trips into Kentucky, Virginia, and West Virginia revealed music that fell outside the written manuscript tradition: fiddle breakdowns, banjo tunes, blues fragments, and work songs shaped by labor and place.

One of the most influential field recordings came in 1937 when Alan Lomax recorded Kentucky fiddler William H. Stepp performing “Bonaparte’s Retreat.” Stepp played an energetic version that caught Lomax’s attention immediately. Four years later, composer Aaron Copland used Stepp’s melody as the basis for “Hoe-Down” in his ballet Rodeo, introducing the tune to audiences far beyond the mountain region.

Researchers know Stepp grew up in difficult circumstances, though the details of his early life vary among local accounts. The historical record becomes clear in his recorded performances, which show a skilled fiddler with a strong sense of timing and variation. His version of “Bonaparte’s Retreat” remains one of the defining examples of Appalachian fiddle music.

Writer and musician Sean Dietrich has retold Stepp’s story in a modern video that mixes period photographs with his own performance of the tune. His presentation gives readers a sense of how a single field recording could travel from a small Kentucky community to an orchestra stage.

A modern retelling of William H. Stepp’s 1937 recording of “Bonaparte’s Retreat,” first captured by Alan Lomax.

How The Efforts of Appalachian Song Catchers Shaped the Crooked Road

Today’s musicians along the Crooked Road draw from a body of songs shaped by these early collectors. Ballads Sharp heard in Madison County are still sung in Galax. Fiddle tunes recorded by Lomax appear in jam sessions across the region. Many younger players learn versions that trace directly back to those first manuscripts and discs.

Preservation brings complexity. Once a song is written down or recorded, it takes on a fixed form. Future singers may return to that version even if other local variants once existed. Yet without the work of the early song catchers, many of these tunes would have faded from memory. Their notebooks and recordings form a spine that holds the tradition in place.

The Legacy of Appalachian Song Catchers

Before collectors reached the mountains, the music depended entirely on memory. A singer might forget a verse. A family might move away. A tune might fall out of use. The song catchers arrived at a turning point when recorded sound was rare, and written notation was even rarer. Their efforts created a record of a culture that valued singing as part of daily life.

Their work also shows how influence moves in surprising ways. A fiddler in Kentucky played a tune for a field collector. That tune traveled into a composer’s studio. It reached concert halls and became part of the national soundscape. Meanwhile, musicians along the Crooked Road continued to play their own versions, shaped by community and place.

Inside Their World

To catch a song required time, patience, and a willingness to listen. The collectors stepped into homes where tunes had been carried for generations. They wrote down what they heard or held a microphone close enough to catch the scrape of a bow. Their work allows today’s musicians and listeners to hear echoes of the past with clarity.

The world of the Appalachian song catchers was built on attention to detail and respect for the people who shared their music. The songs remain alive because someone took the time to listen, one verse at a time.

More Appalachian History & Culture

Find more stories from the region’s past on the History and Culture page.

Appalachian History and Culture Collection

Enjoying Blue Ridge Tales? I hope so. If you’d like to help keep the site ad-free and the stories rolling, you can buy me a coffee.

To stay connected, subscribe to my Blue Ridge Tales newsletter, and have stories and updates delivered once a month to your inbox.