When the Parkway Came to Rock Castle Gorge

An installment in our Blue Ridge Travel series.

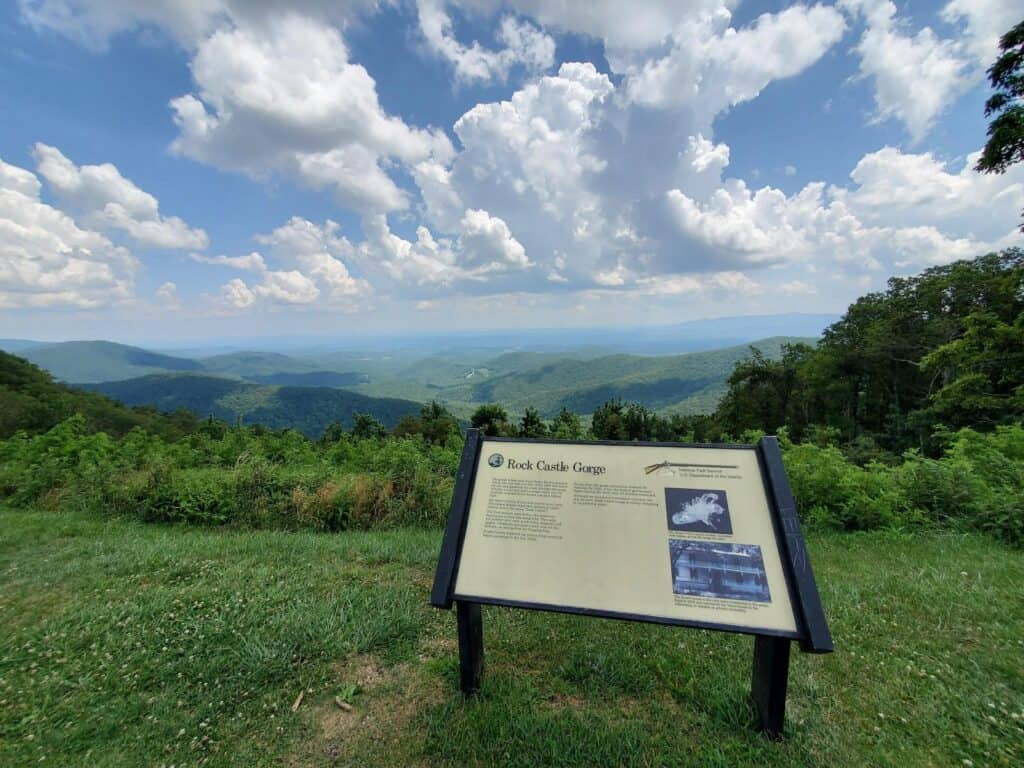

From the pull-off near Rocky Knob, Rock Castle Gorge lies open below the Blue Ridge Parkway. Ridges step down into the valley where families once farmed and built their homes. Most visitors see only the view, not the community that once filled the hollow.

When the Blue Ridge Parkway arrived in the 1930s, it changed the map and the lives implicit in it. The federal plan called for a road with public land on each side. Virginia condemned private tracts and transferred them to the National Park Service. The Rock Castle Gorge section became part of the Rocky Knob Recreation Area. Notices went out. Some families began to pack; others refused to leave.

Money followed, but it rarely covered what was lost. Survey lines split crop fields. Old lanes closed, and access disappeared. A working farm was divided by new boundaries. From the overlook today, it’s hard to match the quiet view with the life that once filled it. A road built for travel and beauty passes over ground that once fed and sustained the people who lived here.

The Government’s Dream of a Scenic Highway

The Blue Ridge Parkway began as a New Deal project. Washington wanted a road that would connect Shenandoah National Park with the Great Smoky Mountains. It would put men to work and open the Blue Ridge to travelers. The idea looked good on paper—jobs, tourism, and a public landscape that showed the best of the mountains.

Engineers surveyed the ridges for a route that followed the high ground. Designers talked about curves that moved with the land and overlooks that framed each view. They called it “a museum of the American countryside.” To make that vision real, the land beneath it had to be cleared of private owners.

Most people outside the region saw the Parkway as progress. In Richmond and Washington, it was praised as an opportunity. In Floyd and Patrick Counties, it felt different. The plan looked orderly on paper. The lives it affected were anything but. Land deeds crossed through generations. Fences ran by memory as much as by line. When the surveyors came through, those old boundaries no longer mattered.

That was the beginning of what happened in Rock Castle Gorge: a collision between a federal promise and the people who stood in its path.

Eminent Domain in the Gorge

Virginia law allowed the state to take land for the Parkway through eminent domain. Families received letters explaining the process and the compensation to be offered. Some agreed quickly, expecting the new road to help them reach markets. Others held out, not believing the government would take land that had never been for sale.

When the condemnations began, people learned what the law meant in practice. Checks came, but they rarely matched the value of what was lost. Some owners received half of what their property was worth. Others got nothing for crops still in the ground or for fences, tools, and livestock left behind.

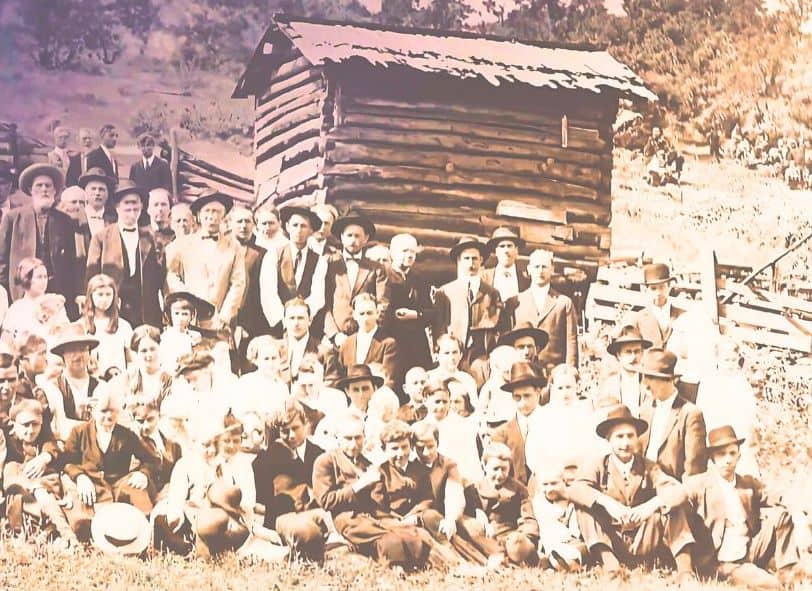

The orchards and farms around Rock Castle Creek had supported families for decades. They grew apples, corn, and garden crops. They kept cattle and hogs and sold what they could. When the road cut through the valley, it split the land into pieces that no longer worked together. Most could no longer make a living from their land.

The People Who Fought to Stay

A few families tried to hold on. They appealed their cases or refused to leave until forced out. The arguments were simple. They wanted fair payment. They wanted to stay on land that had been theirs for generations. They wanted to keep their homes, their churches, and the graves of their families nearby.

Some had been told that the Parkway would serve local needs—a farm-to-market road that would help move goods to town. When they learned it would be limited to travelers, the sense of betrayal ran deep.

How Officials Justified the Uprooting

Federal and state officials defended the process as necessary and beneficial. Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes said the displaced families would be “better off” once relocated. In his view, modernization outweighed sentiment. That message was repeated in official reports and public statements designed to quiet criticism.

The government’s portrayal of mountain residents as poor or backward shaped the public’s perception of the project. It suggested that removal was a kind of rescue. In practice, the people of Rock Castle Gorge were neither helpless nor waiting to be saved. They lived by work, by land, and by habit. Those things could not be replaced with a check.

After the Evictions

When the last families left, the valley fell silent. Homes were dismantled or burned. Cemeteries remained, but roads to them closed. Livestock was sold or driven off. Within a few years, forest began to cover the cleared ground. Visitors who came later saw only trees and stone foundations.

Families scattered. Some found new land nearby; others moved to towns or left the state. The connection to that place—its farms, water, and graves—was broken. The trauma of being removed from ancestral ground stayed with them and with their children.

From the overlook, it’s hard to imagine the history in the view. The quiet there is the result of removal, not time.

Remembering the Rock Castle Families

In recent years, new work has begun to recover what was lost. The documentary Rock Castle Home tells the stories of families forced out during the Parkway’s construction. It records their voices, photographs, and memories before they fade.

The Blue Ridge Heritage Project has built stone-chimney monuments in counties affected by federal takings for parks and parkways. Each monument carries the names of families who once lived there. Oral history programs at Virginia universities and the National Park Service continue to collect interviews from descendants. These efforts have restored recognition, though they cannot undo the loss.

What We Choose to Remember

At the overlook, people stop to rest or take pictures. The wind moves through the grass, and cars pass in both directions. The view is what they came for, but the story behind it still matters.

The Blue Ridge Parkway stands as one of America’s most admired public works. It also stands on the cleared ground of families who once called these ridges home. But the story of Rock Castle Gorge persists. Knowing its story doesn’t lessen the beauty. It gives it context. Both the view and the loss are part of the same tale.

More Blue Ridge Travel

Find more travel stories, routes, and small-town stops on the Blue Ridge Travel page.

View the Blue Ridge Travel Collection here

Enjoying Blue Ridge Tales? I hope so. If you’d like to help keep the site ad-free and the stories rolling, you can buy me a coffee.

To stay connected, subscribe to my Blue Ridge Tales newsletter, and have stories and updates delivered once a month to your inbox.