Mabry Mill: A Blue Ridge Parkway Delight

An installment in our Blue Ridge Travel series.

Photo by Teresa Maybaum

The moonshine still’s cook pot sits down the hill by the creek, mounted atop a stone furnace. The copper tubing leading to the cooling barrel is green with verdigris. The wooden chute that carried water to cool the steaming moonshine is green with moss, but the mash barrels look almost new. The U.S. government once went to great lengths to destroy stills like this one. Now, they’re paying to maintain this historic still.

I take a photo of the still and the sign describing the whiskey-making process. I joke about stealing the government’s moonshine recipe. “Let me know how that works for you,” the Park Ranger grins.

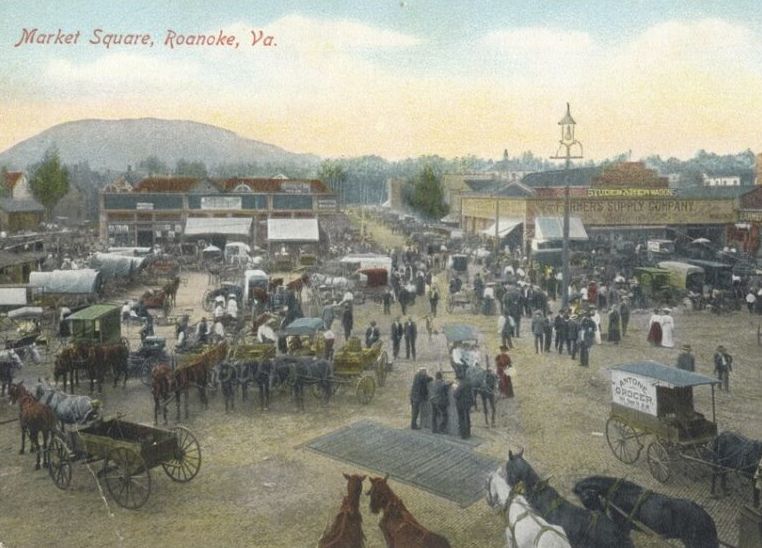

Photo by Wayne Jordan

I’m at Mabry Mill, mile marker 176 on the Blue Ridge Parkway. The Mabry moonshine still is one of many displays intended to give a snapshot of rural Virginia life in the early 20th century. The displays include the famous grist and sawmill, wheelwright shop, blacksmith shop, restored cabins, and more. In addition to the historic displays, there is a gift shop and a restaurant. The restaurant is famous for its buckwheat pancakes, but if you want a real treat, try their “cakes & barbecue” for lunch.

During the season from May through October, park volunteers offer demonstrations of rural skills like soap and molasses making. Twice a year, a visitor can see the grist mill in operation. Today’s volunteer docent at the grist mill speaks knowingly of the inner secrets of the mill: “All she needs to run everything (the lathe, jig saw, tongue & groove router, and sawmill) is new belts, a couple of gears, and some grease.” To someone addicted to the smell of cut wood as I am, my imagination immediately took hold of his description. In my mind’s eye, I could see the belts spinning, hear the saw blades as they bite into the lumber, and sense the acrid-sweet smell of freshly cut wood. The docent’s enthusiasm for the mill made me want to roll up my sleeves, grab a board, and start cutting.

The “rural skills” demonstrations leave the Mabry Mill visitor with a romantic notion of mountain life in the early part of the twentieth century. The truth is that the Mabry’s and their neighbors were isolated from most commercial sources of supply, and if something was needed, they usually had to make it themselves or do without. If something broke, they fixed it themselves but had to find a local source for hardware and parts. Need some nails? Ed Mabry would make them for you. Need a wheel for your wagon? Ed Mabry would make you one. Need lumber to build a house? See Ed. Mabry’s place was a mountain version of Home Depot.

The independent and self-reliant nature of the early Scots-Irish settlers is still evident in the people of the Blue Ridge Mountains today. Sufficient paved roads and electricity didn’t arrive until after WWII, so the folks here grew up caring for their needs. My farming neighbors in Meadows of Dan seem to be able to fix anything. Contrast their skill set to my Washington, DC neighbor who claimed that a properly conjured stream of profanity and a swift blow with a wrench could fix almost anything.

Mabry Mill is more than a scenic stop along the Parkway. It’s a testament to the ingenuity and resourcefulness of the men and women of the Blue Ridge Mountains. It’s also a darned good place to have buckwheat cakes and barbecue.

More Blue Ridge Travel

Find more travel stories, routes, and small-town stops on the Blue Ridge Travel page.

View the Blue Ridge Travel Collection here

Enjoying Blue Ridge Tales? I hope so. If you’d like to help keep the site ad-free and the stories rolling, you can buy me a coffee.

To stay connected, subscribe to my Blue Ridge Tales newsletter, and have stories and updates delivered once a month to your inbox.