Forgotten Spaces: Appalachian Poorhouse Farms

An installment in our Appalachian History and Culture series

Before the days of welfare programs and safety nets, communities had to find ways to care for their most vulnerable. Appalachia was no different. Scattered throughout the hills and valleys of this rugged region, poorhouse farms were an essential part of the social fabric, though rarely spoken of today. These farms served as both a refuge and a reminder of society’s struggle with poverty. In this place, the elderly, mentally ill, and destitute lived and worked. But the story of poor farms isn’t just about institutions; it’s about people. People who, for one reason or another, found themselves on the fringes, left to survive in a system that was equal parts charity and punishment.

The Origins and Purpose of Poorhouse Farms

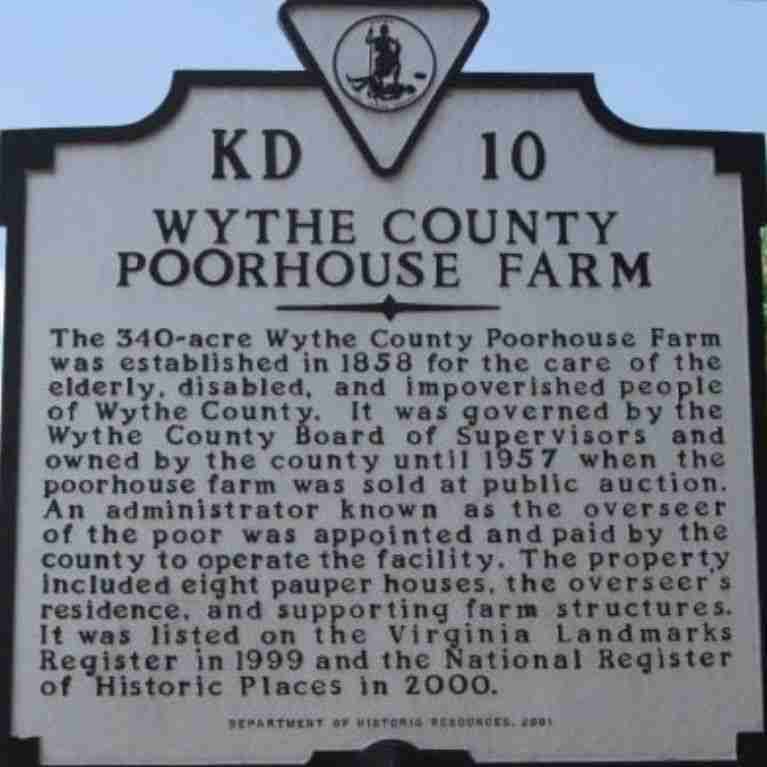

The poorhouse farm concept was born out of necessity. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, before the rise of Social Security and other social welfare programs, many counties across the United States faced the pressing question of what to do with people who couldn’t support themselves. Poorhouse farms became the answer in rural areas like Appalachia, where resources were scarce and family networks were often stretched thin.

Poorhouse farms, or “almshouses” as they were sometimes called, were typically funded by local governments. The idea was simple: instead of giving money or food to those in need, counties established farms where the poor could live and work. Residents provided labor, often in agriculture, and the produce generated helped sustain the farm. In return, they received shelter, food, and a semblance of stability.

While the setup sounds practical, it was far from idyllic. Poorhouse farms were often viewed as a last resort, a place for those without other options. The elderly, the sick, and those deemed mentally unfit were housed alongside able-bodied men and women who had fallen on hard times. While functional on paper, it was a mix that created a complex and often grim living situation.

Life on the Farm

Life on a poorhouse farm wasn’t easy. In some records, residents—called “inmates” were expected to earn their keep. This wasn’t a place for idle hands. The able-bodied were tasked with maintaining the farm: planting crops, tending livestock, repairing buildings, and in some cases, producing items like soap or furniture to be sold for extra income. It was a self-sustaining system, though the work was hard, and the rewards were few.

Men typically handled most of the physical labor, but women also contributed. They often worked in the kitchen, tended to small animals, or helped with cleaning and laundry. For many, the work was relentless, and the sense of isolation could be profound for those who were too old or infirm to help.

But it wasn’t just the physical demands that made life difficult. There was a deep stigma attached to living on a poor farm. In many communities, being sent to a poor farm was seen as a failure, a mark of shame that stuck with families for generations. The poor were often viewed as morally deficient, and the very existence of these farms reinforced the idea that poverty was something to be hidden away, out of sight and out of mind.

Yet, despite the harsh conditions, poorhouse farms were, for some, a lifeline. For the elderly with no family left to care for them or for those who had been shut out by society, it was a place to survive. The residents often formed their own makeshift families, finding solidarity in their shared hardship. These farms were far from ideal, but they were the only option for many.

Societal Views and Stigmas

The stigma surrounding poorhouse farms wasn’t just about poverty but about how society viewed the poor. In the early 20th century, poverty was often seen as a personal failing rather than a systemic issue. This mindset influenced how people were treated on poor farms. The residents were expected to work not just because the farm needed labor but because there was a prevailing belief that work would reform them. If someone was poor, the thinking went, hard work would set them straight.

This created a tense environment. Many residents were elderly or sick, unable to contribute in the ways the system demanded. For them, the poor farm became less of a place of rehabilitation and more of a prison. The societal attitudes toward these individuals were often harsh. While some counties saw poor farms as a necessary form of charity, others viewed them as dumping grounds for society’s “undesirables.”

Over time, as federal programs like Social Security and public assistance grew in the 1930s and ’40s, the need for poorhouse farms began to decline. But the cultural memory of these farms—and the stigma attached to them—lingered for decades.

The Decline of Poorhouse Farms

The Great Depression and the subsequent rise of government welfare programs marked the beginning of the end for poorhouse farms. Social Security, unemployment benefits, and public housing initiatives gave people more options. Suddenly, the elderly and unemployed didn’t have to rely on local governments to provide a roof over their heads or food on their tables.

As these federal programs expanded, poor farms began to shut down. Many buildings were repurposed into nursing homes or prisons, while others fell into disrepair. The farms that had once been vital to the social infrastructure of Appalachian counties became relics of a bygone era.

Some counties tried to adapt their poor farms to modern care facilities, but the stigma remained. The old attitudes about poverty and the people who had lived on these farms were hard to shake. Even as the physical structures decayed, the cultural memory of poor farms continued to cast a long shadow over communities.

The Legacy of the Farms in Appalachian Memory

While poor farms have mostly faded from the landscape, their legacy endures in Appalachian memory. Many older generations remember hearing stories about relatives who lived or worked on these farms. In some communities, poor farms became part of local folklore, woven into the fabric of regional history.

Poverty remains a pressing issue in modern Appalachia, but how we approach it has changed. Welfare programs, non-profits, and community initiatives have replaced poor farms, but the struggles of rural poverty persist. The story of poor farms reminds us how far we’ve come—and how far we still have to go. It also offers an uncomfortable reflection on how society has historically treated its most vulnerable citizens.

Lessons from Appalachian Poorhouse Farms

Poorhouse farms may seem like a relic of a distant past, but their story is still relevant today. They serve as a reminder that poverty isn’t a new problem nor one that can be easily solved. The residents of poor farms were people—people who, for various reasons, fell through the cracks of society.

As we look back on the history of poorhouse farms in Appalachia, we’re confronted with tough questions about how we care for the poor, the elderly, and the disabled. Have we moved beyond the stigmas surrounding poverty, or do we still judge those who struggle to make ends meet? While we no longer send people to poor farms, the issues these institutions addressed are far from resolved. Perhaps the lesson of poor farms is that while charity and care are necessary, compassion and understanding are just as vital.

It’s a lesson that, even today, we’re still learning.

More Appalachian History & Culture

Find more stories from the region’s past on the History and Culture page.

Appalachian History and Culture Collection

Enjoying Blue Ridge Tales? I hope so. If you’d like to help keep the site ad-free and the stories rolling, you can buy me a coffee.

To stay connected, subscribe to my Blue Ridge Tales newsletter, and have stories and updates delivered once a month to your inbox.