The Salt Trade on the Holston River: A Frontier Lifeline

An installment in our Appalachian History and Culture series

Life on the early frontier often hinged on one thing: salt. It preserved food, kept animals and humans healthy, and was used as trade currency. Great battles were fought over it. Men died mining it. The salt trade on the Holston River wasn’t just a business; frontier economies rose and fell with the availability of salt.

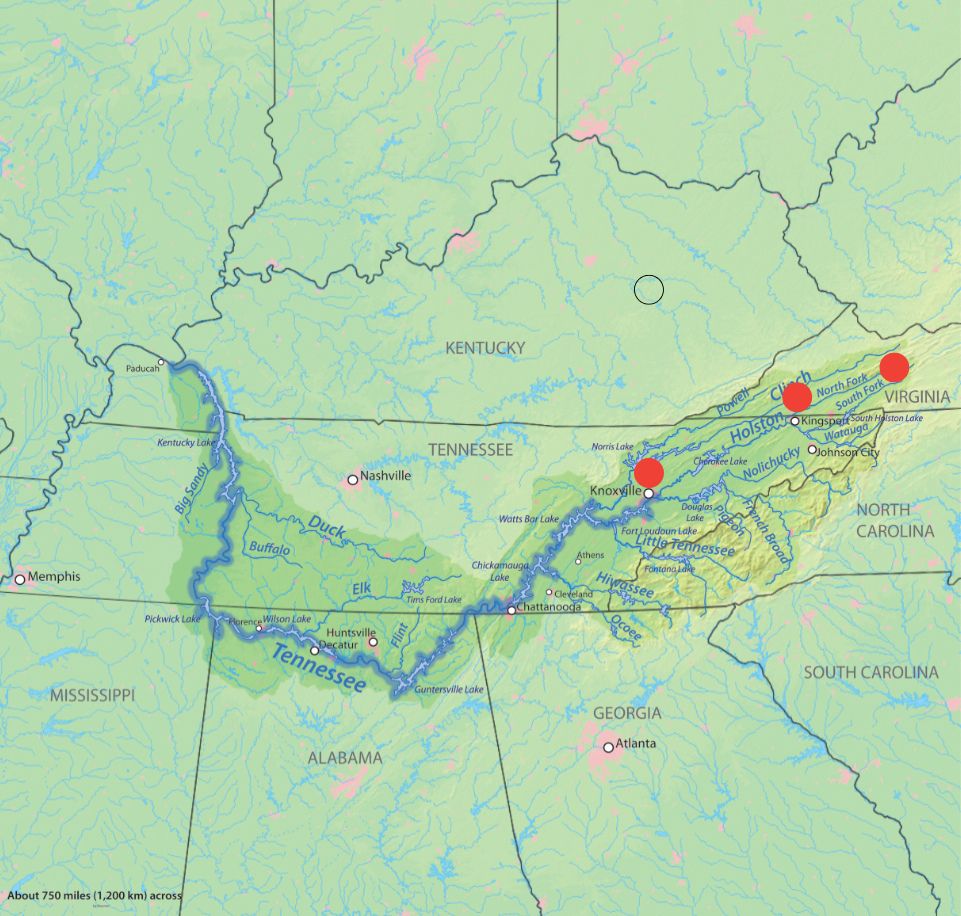

Before railroads cut through the mountains, the Holston was the region’s main highway, carrying barrels of salt from southwest Virginia’s rich brine deposits to markets downriver. From the mines of Saltville to the trading hubs of Kingsport and Knoxville, salt shaped economies, communities, and even the course of history.

The Source: Saltville’s Briny Bounty

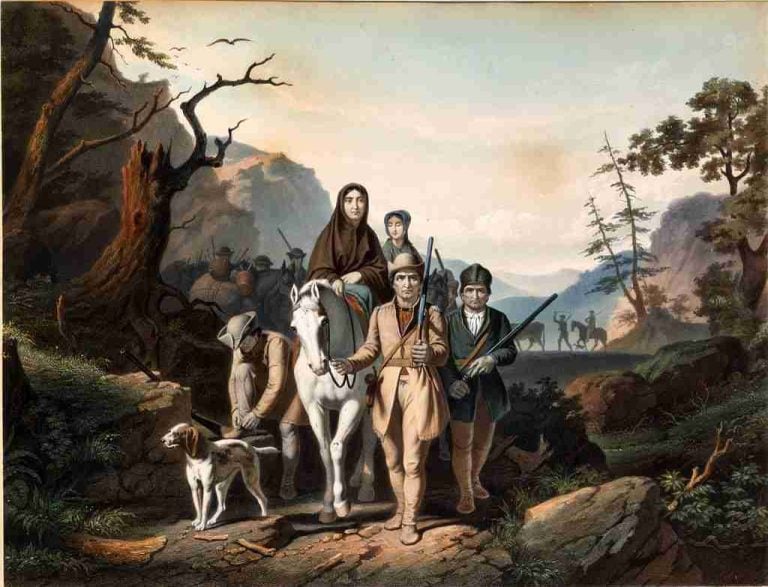

Before settlers and traders turned Saltville into an industrial hub, the area’s vast salt deposits had attracted life for millions of years. Prehistoric animals, including mastodons and mammoths, were drawn to the mineral-rich springs, leaving behind fossil evidence of their presence. Indigenous peoples later established salt-harvesting methods, recognizing the site’s significance for food preservation and trade. By the time European settlers arrived, they were tapping into a resource that had been sustaining life for millennia.

Saltville, Virginia, was the beating heart of the salt trade in the Blue Ridge Mountains. Underground brine deposits made it one of America’s prime mineral sources. Workers pumped brine from wells and boiled it down in massive kettles, leaving behind mineral crystals. The salt was packed into heavy wooden barrels, transported to the river, and, eventually, the tables of settlers and soldiers alike.

By the early 1800s, Saltville was a round-the-clock operation, with kettles bubbling 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Manufacturing required a massive supply of fuel for the fires, cooperage shops to supply barrels, and housing and tradesmen to support the growing town. The demand never slowed—livestock drovers, traders, and military suppliers all counted on a steady supply. But mining salt was only half the job. A more serious challenge was getting it to market.

The Journey: Salt’s Path Down the Holston River

Transporting salt wasn’t for the faint of heart. Keelboats and flatboats, piled high with barrels, pushed off from Saltville, riding the river’s current toward trading centers downstream. It was a slow and risky business—river pilots had to navigate twisting channels, dodge sandbars, and stay ahead of sudden floods.

Kingsport was the first major stop. Here, traders resupplied, swapped goods, and sometimes offloaded barrels for local markets. Those continuing to Knoxville had to brace for an unpredictable ride. Along the way, riverside merchants set up shop, eager to trade salt for whatever goods they could get—corn, hides, whiskey, or even cash when it was available. Every stop along the Holston was a chance to turn salt into something more.

Weather and the Hazards of the River

Navigating the Holston required an intimate knowledge of the river’s bends and how to survive its moods. Spring rains could swell the river, making the current fast and treacherous, sweeping away boats and cargo with little warning. High water brought hidden debris, adding to the risk.

Winter, on the other hand, could grind everything to a halt. Ice made river sections impassable, forcing traders to wait for a thaw. Even when the river remained open, freezing temperatures made handling the salt barrels miserable. Despite these challenges, traders adapted, timing their shipments to the seasons and taking calculated risks when necessary.

Markets and the Demand for Salt

When salt shipments reached Knoxville, they connected to a much wider trade network. From here, salt spread west into Kentucky, south into Georgia, and deeper into the growing frontier. Salt was currency. Bartering was common, and a single barrel of salt could bring stacks of animal pelts, sacks of grain, or hard cash. Without it, food spoiled quickly, making it one of the most valuable resources in frontier life.

The Decline of the Salt Trade on the Holston River

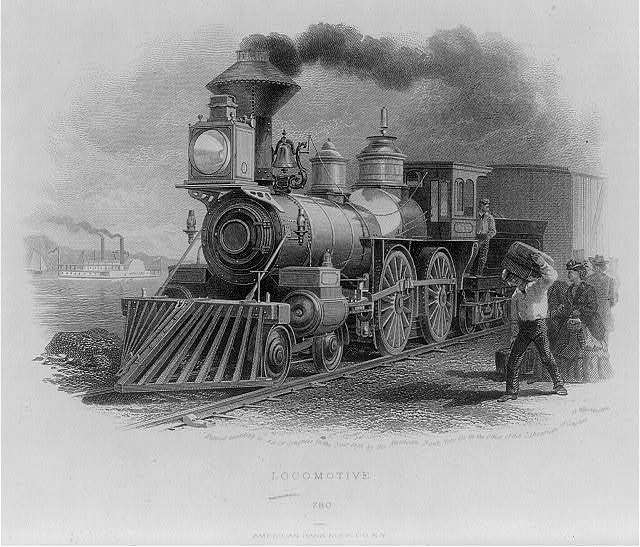

For years, the salt trade on the Holston River kept frontier economies alive. But progress has a way of reshaping things. When railroads began carving through the mountains, the riverboats lost their dominance. By the mid-19th century, trains made moving goods faster, cheaper, and more reliable. The days of salt-laden boats drifting down the Holston were numbered.

Saltville stayed in business well into the Civil War, producing for the Confederacy until Union forces targeted it. After the war, the Saltville saltworks were transformed by developing chemical industries and railroads. Riverboats disappeared, and with them, an era of frontier commerce faded into memory.

Echoes of the Past

The Holston River still winds through Virginia and Tennessee, quieter now than in its heyday. Once, its waters carried the lifeblood of the frontier—barrels of salt bound for distant markets, guided by men who knew every bend and current. The salt trade may be history, but its legacy lingers in the towns and roads that grew up around it: Gate City (VA), Kingsport (TN), Rogersville (TN), and Knoxville (TN).

The salt trade on the Holston River shaped economies, migration patterns, and even how people lived their daily lives. The river no longer carries barrels of salt to market. Still, if you listen closely, you might just hear the echoes of boatmen and traders who once made their living on its waters.

More Appalachian History & Culture

Find more stories from the region’s past on the History and Culture page.

Appalachian History and Culture Collection

Enjoying Blue Ridge Tales? I hope so. If you’d like to help keep the site ad-free and the stories rolling, you can buy me a coffee.

To stay connected, subscribe to my Blue Ridge Tales newsletter, and have stories and updates delivered once a month to your inbox.