The Wilderness Road: Daniel Boone’s Gateway to the West

An installment in our Appalachian History and Culture series

The Road That Changed America

Imagine standing at the edge of civilization, your worldly possessions packed onto a horse, your family by your side. The road ahead is no more than a rough footpath, cutting through dense forest and winding toward a mountain pass. You’ve heard the stories—of fertile land beyond the mountains, danger lurking in the woods, and families who never made it through. Yet here you are, ready to take your chances on the Wilderness Road.

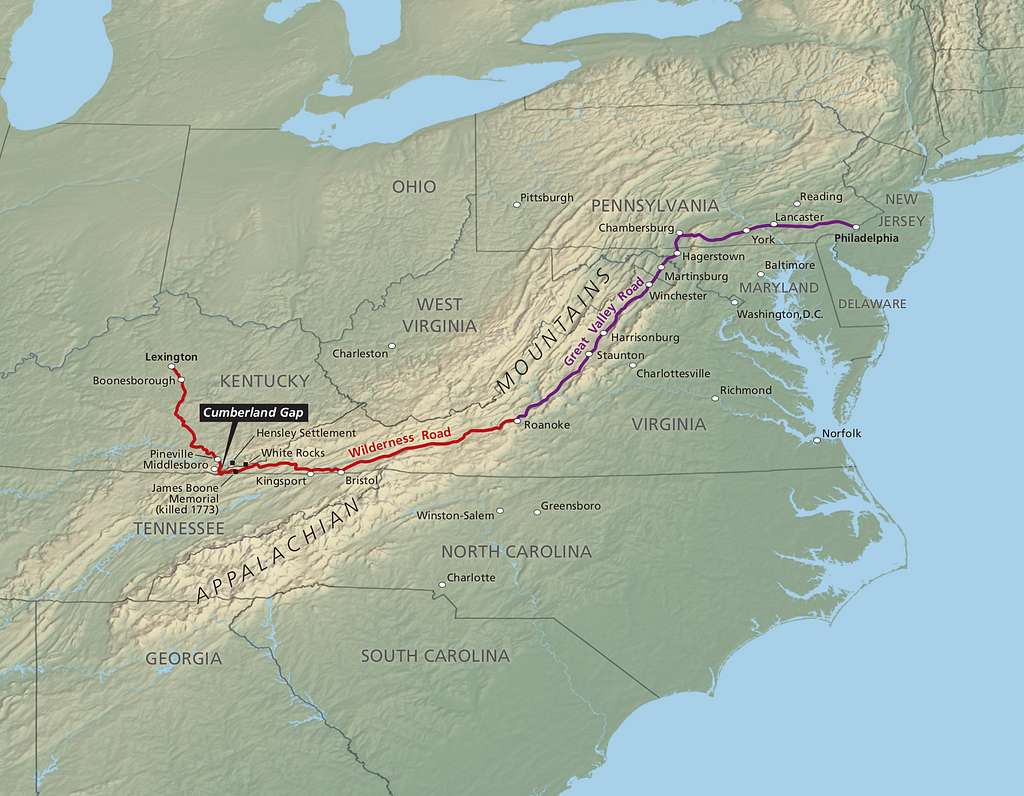

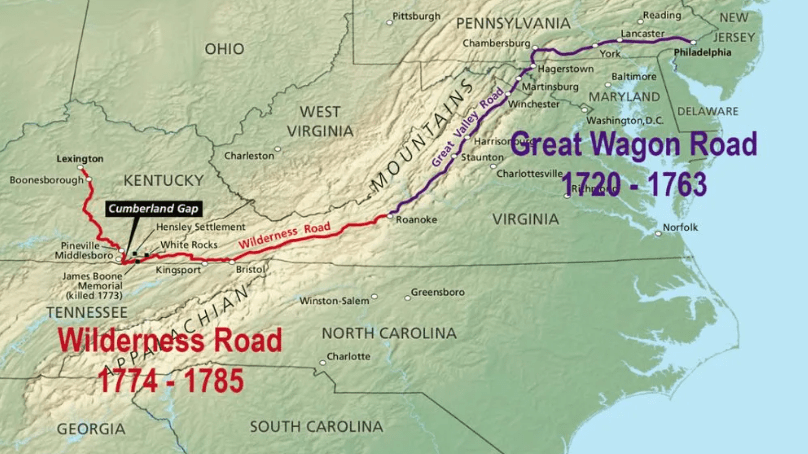

For thousands of settlers in the late 18th century, the Road wasn’t just a trail—it was a gamble, a test of resilience, and a one-way ticket to the frontier. Blazed by Daniel Boone in 1775, it provided the first major route through the Appalachian Mountains, opening Kentucky and beyond to settlement. But before travelers could even set foot on the trail, they had to make it to Fort Chiswell, Virginia, the last civilized outpost before the long, treacherous road west.

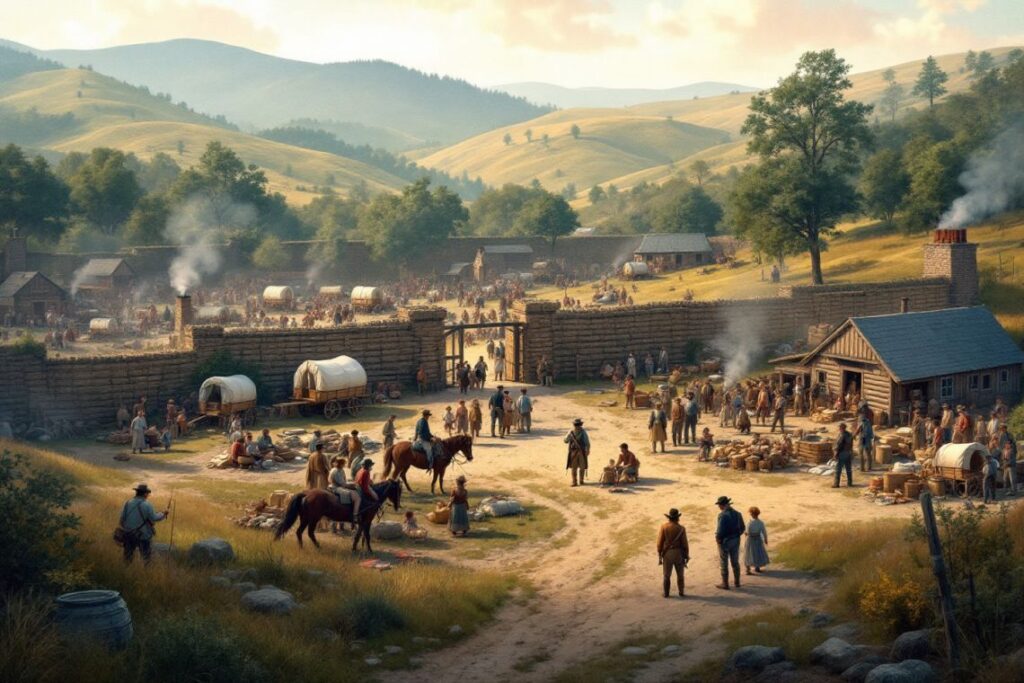

Fort Chiswell: The Last Stop Before the Unknown

Long before Kentucky became the “West” in American minds, Fort Chiswell stood as the final supply post on the way to the frontier. Built in 1758 during the French and Indian War, the fort sat at a critical crossroads where the Great Wagon Road, the Great Valley Road, and the newly forming Road through the wilderness intersected. By the 1770s, it had become more than a military outpost—it was the assembly point for those willing to leave everything behind in search of a new life.

Here, families prepared for the brutal journey ahead. Supplies were purchased, wagons were abandoned (since the rough road beyond was barely wide enough for a pack horse), and groups formed for safety in numbers. Travelers traded news of recent attacks, sorted out possible dangers, and debated whether they were ready to cross into the unknown. Some turned back. Others pressed forward, trusting their lives to Boone’s trail.

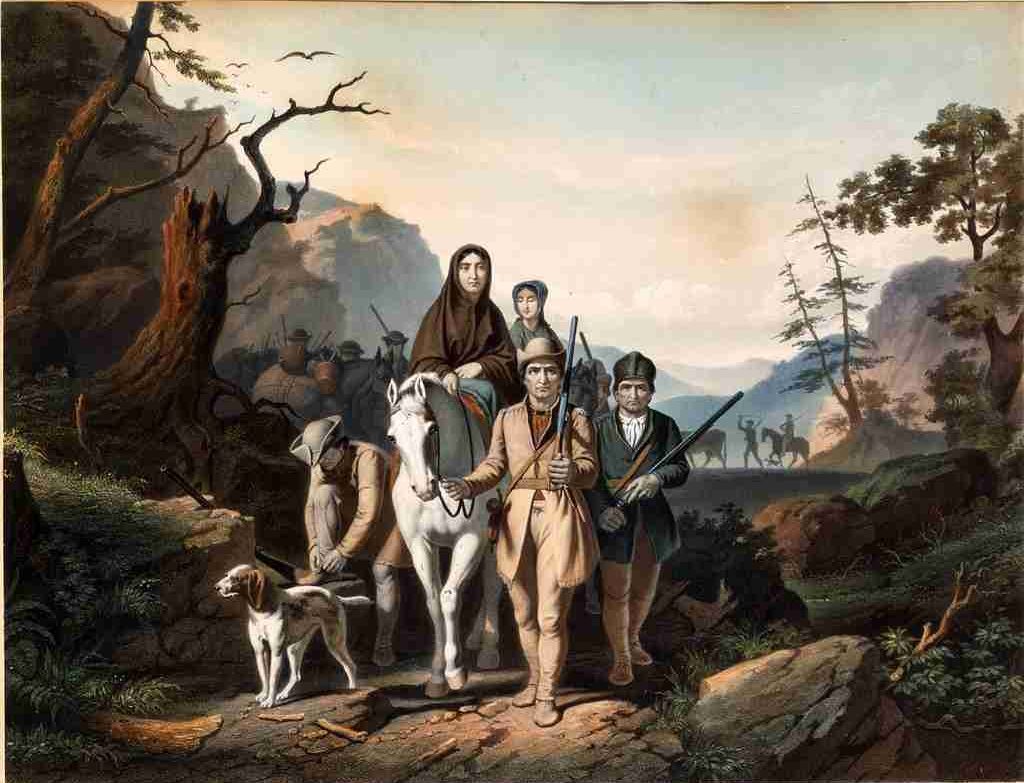

Daniel Boone and the Blazing of the Wilderness Road

By the time Boone and his team of axmen hacked through Cumberland Gap in 1775, the Appalachian Mountains had stood as an impenetrable barrier for most settlers. Unlike the Great Wagon Road, which moved south along the Blue Ridge, the Road was the first major path to cut westward through the mountains, creating a direct route into Kentucky.

Boone’s job wasn’t easy. He and his men carved a narrow, winding trail through the thick wilderness, widening what had once been a Native American footpath. The work was backbreaking, the dangers constant—hostile Shawnee warriors viewed settlers as invaders, and wild animals roamed the forests. Yet despite these obstacles, Boone succeeded. By the end of 1775, the Wilderness Road stretched from Fort Chiswell, Virginia, through Cumberland Gap and into the newly founded settlement of Boonesborough, Kentucky.

With a way open to the west, the migration floodgates burst wide.

The Harsh Reality of the Journey

Romantic notions of frontier life often ignore the brutal realities of the Road. Unlike the more developed Great Wagon Road, this path was little more than a crude trail through untamed wilderness.

The Terrain Was Unforgiving – Travelers faced narrow mountain passes, deep river crossings, and thick forests where a wrong turn could mean being lost for days. Wagons were impractical, forcing families to carry only what they could pack onto horses or their backs. Most food was hunted or foraged along the way.

Hostile Encounters Were Frequent – The Shawnee and other Native American groups, angered by the encroachment on their lands, launched raids along the road. Many settlers never made it to Kentucky.

Disease and Starvation Took Their Toll – Clean water was scarce, food supplies ran low, and those who became ill often had no choice but to be left behind.

Those who survived found themselves in Kentucky, a land of opportunity—but also of continued struggle.

The Impact of the Wilderness Road

Despite its dangers, the Road was one of the most significant routes in American history. By 1800, over 200,000 settlers had used it to reach Kentucky, transforming the region from an isolated wilderness into a bustling frontier. The influx of pioneers led to Kentucky’s statehood in 1792, marking the first permanent step in America’s westward expansion.

In time, safer and wider roads would replace Boone’s rough trail, but the Road set the precedent. It proved that the Appalachian barrier could be crossed, paving the way for later migrations along trails like the Oregon Trail and the Santa Fe Trail.

Tracing the Road Today

For those who want to walk in the footsteps of the pioneers, much of the Wilderness Road can still be explored today:

✨ Cumberland Gap National Historical Park – Visitors can hike sections of the original trail and stand where thousands of settlers passed into Kentucky.

✨ Wilderness Road State Park (Virginia) – A reconstructed 18th-century fort and visitor center offer insights into life on the road.

✨ Modern Highways on the Old Trail – Today, U.S. 25 and I-75 roughly follow Boone’s first blazed route.

Fort Chiswell may be gone, and Boone’s rugged trail may have been replaced by asphalt. Still, the Wilderness Road remains a symbol of the American frontier spirit.

Would You Have Taken the Journey?

Standing at Fort Chiswell in 1780, staring west toward Cumberland Gap, would you have had the courage to go? The families who braved the Road weren’t just seeking land—they were seeking a new life, a fresh start, a future that could only be found beyond the mountains.

Some made it. Some didn’t. But all of the pioneers, in one way or another, shaped the course of American history.

The Wilderness Road wasn’t easy. But nothing worth doing ever is.

More Appalachian History & Culture

Find more stories from the region’s past on the History and Culture page.

Appalachian History and Culture Collection

Enjoying Blue Ridge Tales? I hope so. If you’d like to help keep the site ad-free and the stories rolling, you can buy me a coffee.

To stay connected, subscribe to my Blue Ridge Tales newsletter, and have stories and updates delivered once a month to your inbox.