Paper, Power, and Race in Old Jim Crow Virginia

An installment in our Appalachian History and Culture series

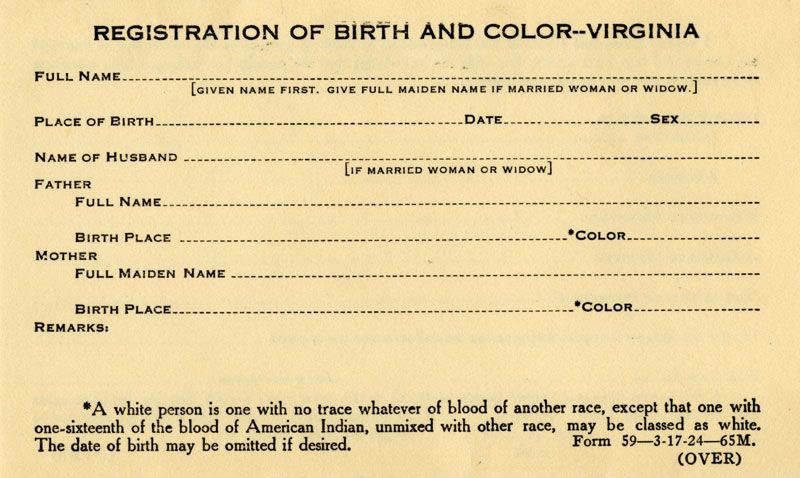

In Jim Crow Virginia, the power of a single piece of paper could decide your future—or erase your past. In 1924, the Commonwwealth of Virginia passed a law that tried to nail down something as messy and human as race using bureaucratic language and the force of law. One drop of the wrong blood, and you weren’t white anymore. Just like that.

The Virginia Racial Integrity Act was part of a national obsession with eugenics (30 states had such laws). But in Virginia, it had a Southern twist. It was about preserving whiteness, yes—but also about control. In a state where families had lived for generations with tangled roots and mixed heritage, especially in Appalachia, the law sliced clean lines where life had drawn messy ones. It broke apart communities. It fractured families. It redrew identities—and the scars still show.

This story isn’t easy to tell. But in Jim Crow Virginia, the question of who was allowed to be “white” wasn’t really about biology. It was about who held the pen.

Drawing Lines: The Birth of Racial Bureaucracy

By the time the Racial Integrity Act was signed into law, the idea that whiteness needed legal protection was already baked into Southern life. But this law made it official. According to the state, you couldn’t be white if you had any ancestry outside of “pure” Caucasian stock. The one loophole? The so-called “Pocahontas clause,” a carve-out for Virginia’s elite who traced their family trees back to Pocahontas and John Rolfe. Without that exception, some of the most powerful families in the state would’ve been disqualified from whiteness.

The law didn’t stop at racial classification. It banned interracial marriage outright. Anyone who crossed the line risked annulment, jail, or having their children reclassified—sometimes overnight.

This wasn’t just a social code. It was a legal infrastructure, one that aimed to reshape the state’s population on paper. Jim Crow Virginia wasn’t just about separate water fountains—it was about separating people down to their bloodlines.

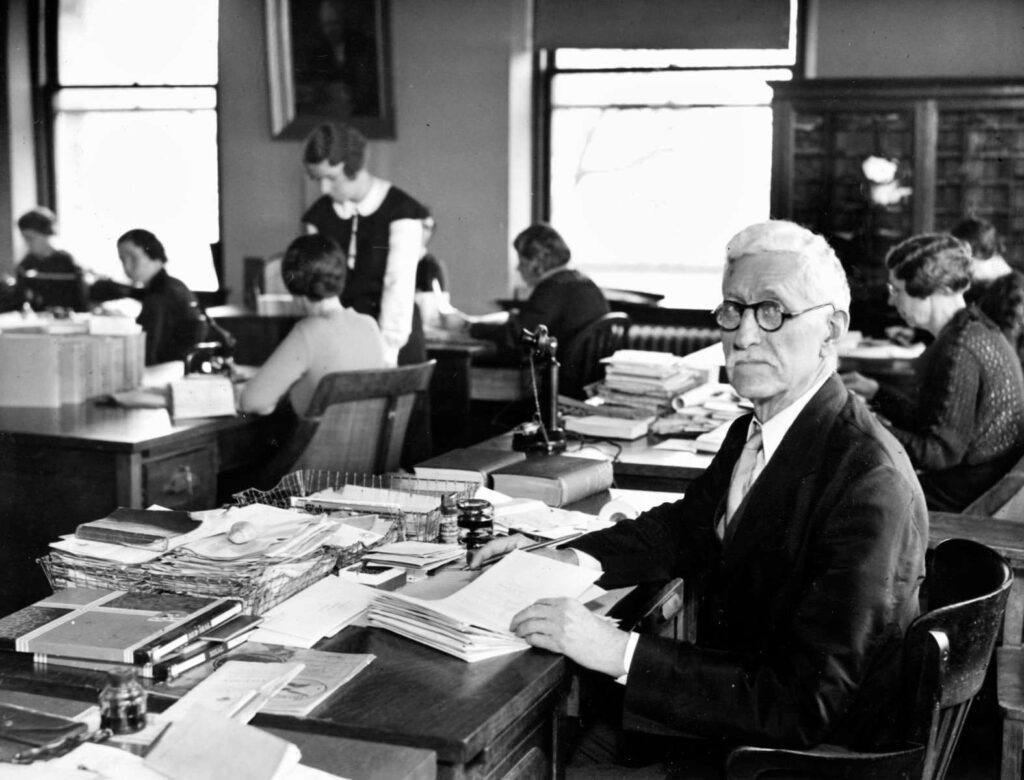

Walter Plecker and the War on Identity

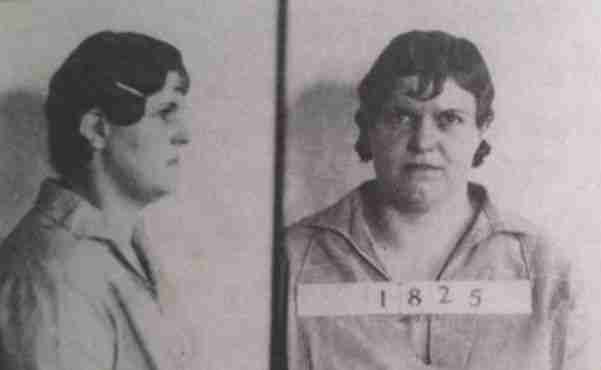

The man behind the curtain was Dr. Walter Ashby Plecker, Virginia’s first registrar of vital statistics. From his Richmond office, he wielded an alarming amount of power over how people were recorded in birth and death documents, marriage licenses, and census forms. And he used it.

Plecker made it his mission to scrub the records clean of anything he saw as racial ambiguity. If someone claimed to be Native American, he often took a red pen to the file and changed it to “colored.” No questions asked.

His campaign targeted Indigenous tribes like the Monacan, Pamunkey, and Mattaponi. These communities had lived in Virginia for centuries—but in Plecker’s eyes, they didn’t count. He called them “mongrels” and considered their claims to Native identity fraudulent. He even sent out lists to county clerks, instructing them not to accept birth or marriage certificates from certain surnames he deemed suspect.

For families in Jim Crow Virginia, the consequences were immediate and painful. Ancestral identities disappeared from official records. Children were taught to deny who they were. Tribal communities lost recognition, and with it, access to schooling, health care, and legal protections. All it took was one man with a desk, a pen, and the full power of the state.

Appalachian Families in the Crosshairs

Nowhere did this law hit harder than in the hills and hollers of Appalachian Virginia. These were tight-knit places where families had lived for generations, often blending Black, white, and Native roots. Folks weren’t filling out family trees to prove their racial status—they were raising kids, growing gardens, and surviving together.

But suddenly, those quiet, tangled histories became liabilities. Under the Racial Integrity Act, some cousins ended up classified differently—one “white,” one “colored”—based on something as arbitrary as skin tone or gossip. Entire communities were rebranded by the stroke of a pen. Some families moved to avoid the fallout. Others simply stopped talking about where they came from.

In Jim Crow Virginia, silence became a survival strategy. And that silence stretched on for decades.

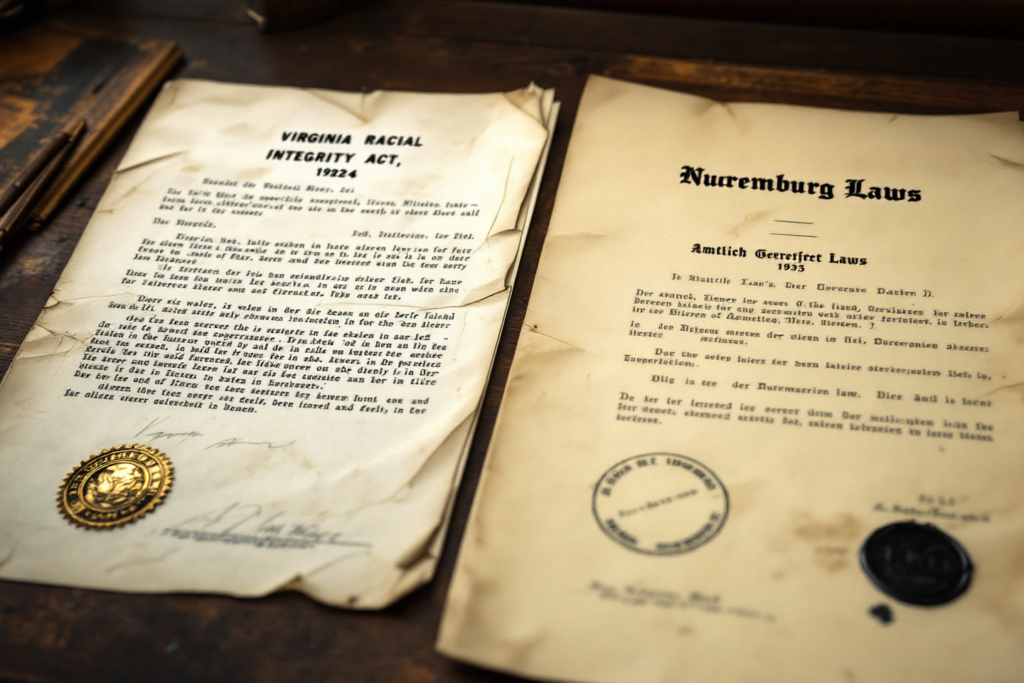

Echoes Across the Atlantic: International Influence

As chilling as it sounds, the influence of the Racial Integrity Act didn’t stop at the state line. In the 1930s, Nazi Germany looked to the United States—especially Virginia and California—as models for its own racial laws. They studied our sterilization statutes. They examined our rules on interracial marriage. And yes, they looked closely at how Virginia defined race.

Dr. Plecker even exchanged letters with top Nazi eugenics officials, including Dr. Walter Gross of Germany’s Bureau for Race Hygiene. In those letters, Plecker praised Germany’s sterilization programs and offered encouragement for their racial policies. It’s hard to overstate how disturbing that connection is.

When the Nazis passed the Nuremberg Laws in 1935, barring Jews from marrying Aryans and setting the stage for genocide, they pointed to American laws—especially those from Virginia—as proof that their policies weren’t so radical after all.

In that sense, Jim Crow Virginia didn’t just export tobacco or textiles. It exported a blueprint for genocide.

Undoing the Damage (But Not Entirely)

The Racial Integrity Act stuck around for more than 40 years. It wasn’t until the Supreme Court case Loving v. Virginia in 1967 that the law was struck down and interracial marriage was finally legalized across the state.

But legal victories didn’t erase decades of damage.

Tribal nations like the Monacan spent years trying to reclaim recognition—fighting not just against ignorance, but against altered records and bureaucratic ghosts. Families found themselves lost in the fog of redacted heritage. And in a world where identity had become a legal risk, many simply never spoke of it again.

Today, a growing number of genealogists, historians, and tribal communities are working to recover what was lost. DNA tests, oral histories, and painstaking document recovery are helping to piece back the puzzle. But it’s slow work. Emotional work. And the wounds aren’t just on paper.

Refusing to Be Redefined

So, let’s go back to that question: what makes a person white?

In Jim Crow Virginia, the answer wasn’t in your skin or your story. It was in your paperwork. It was in the hands of men like Walter Plecker, who believed they could dictate who you were with a few strokes of a pen.

But real identity? That doesn’t come from a form. It comes from your people. Your memories. The stories told at family gatherings. The names passed down through generations, even if they never made it onto a state certificate.

The Racial Integrity Act tried to erase all that. And for a while, it almost did.

But people fought back—sometimes loudly, sometimes silently. They refused to be redefined. They protected what they could. And in doing so, they passed down something the law could never touch: a legacy of endurance.

Not written in ink. Written in lives.

More Appalachian History & Culture

Find more stories from the region’s past on the History and Culture page.

Appalachian History and Culture Collection

Enjoying Blue Ridge Tales? I hope so. If you’d like to help keep the site ad-free and the stories rolling, you can buy me a coffee.

To stay connected, subscribe to my Blue Ridge Tales newsletter, and have stories and updates delivered once a month to your inbox.