The Lost History of Freemen in Appalachia

When most people think of African Americans in the 19th century, two images dominate: Southern slaves or Northern abolitionists. But tucked deep in the hills and hollows of the mountain South, there lived thousands of men and women who didn’t fit either category. They were Freemen in Appalachia—Black Americans who were not enslaved yet not fully free—and their stories have largely been left out of the history books.

The presence of Freemen in Appalachia challenges the conventional narrative of who lived in the region, how they lived, and what freedom really meant. In a place long romanticized as white, poor, and isolated, these communities carved out lives in the spaces between bondage and liberty. And yet, their legacy has been buried beneath layers of myth, neglect, and deliberate erasure.

It’s time to bring it to light.

The Hidden Demographics of Freedom

By 1860, more than 250,000 free Black people lived in the United States—and a surprising number of them lived in the Appalachian South. In places like western Virginia, East Tennessee, and parts of North Carolina and Kentucky, census records reveal small but stable populations of free African Americans. These were not Northern migrants. Many had been born in bondage and later freed or were the descendants of free people of color going back generations.

They were farmers, blacksmiths, preachers, seamstresses. Some owned modest plots of land. Others rented or worked as tenant laborers. In a few cases, they even owned slaves themselves—often, family members purchased them to protect them from re-enslavement in a twisted legal workaround.

Their presence complicates the tidy binaries we’re often taught: free or enslaved, North or South, Black or white. Appalachia, it turns out, held more complexity than many historians once admitted.

The Precarious Reality of Daily Life for Freemen in Appalachia

For all the freedoms they technically held, the lives of Freemen in Appalachia were bound by restriction and risk. In many places, they were prohibited from voting, holding certain jobs, or testifying in court against white people. Laws required them to carry proof of freedom at all times. At any moment, an accusation—true or false—could mean jail, whipping, or worse.

In response, many freemen developed tight community bonds. Churches often served as both spiritual and social anchors. Family networks were essential, especially in protecting children from being stolen or coerced into indenture. Every legal right was tenuous; every hard-won gain could be undone by the whims of white society.

Still, they endured. In small enclaves and backwoods farms, they planted, taught, preached, and raised children who carried the quiet pride of living on their own terms—however narrowly defined those terms might have been.

Stories of Resistance and Resilience

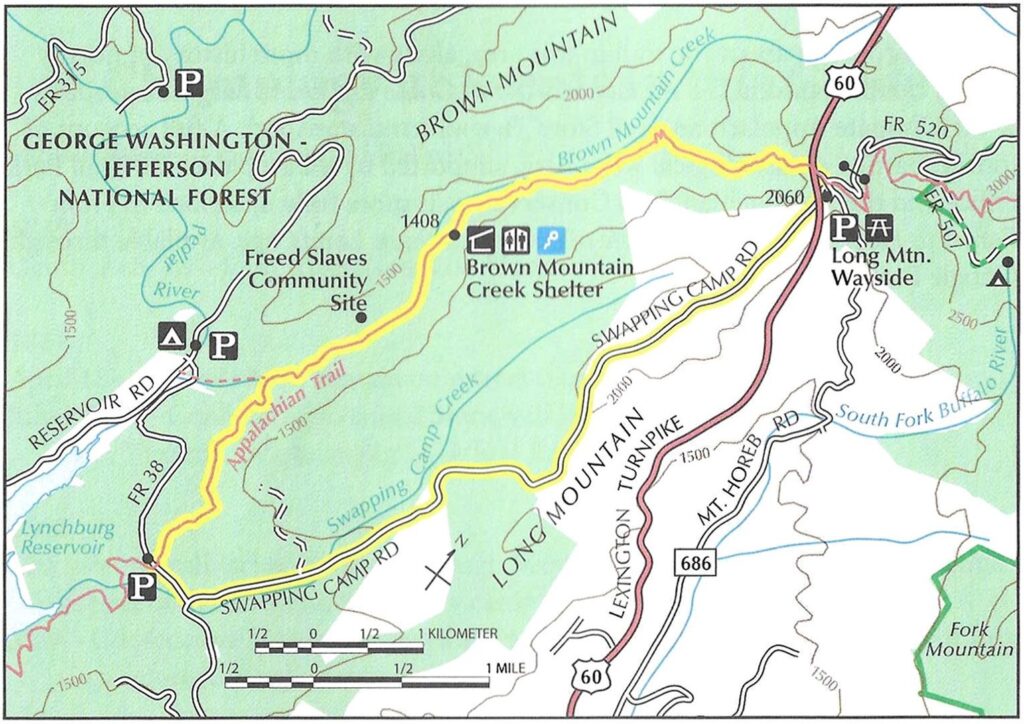

One of the most compelling examples comes from Virginia’s Brown Mountain Creek, where a community of freedmen thrived after the Civil War. One leader, Mose Richeson, bought 220 acres of land and helped build a small village with homes, gardens, and a church. Oral histories tell of families who cooked on stone hearths, shared tools, and tended crops on terraced slopes now grown wild.

Though Richeson’s story is post-emancipation, it echoes earlier patterns: self-reliance, cooperation, and a fierce commitment to land and family. Across Appalachia, other communities shared these values, even if their names were never written down.

Music, food, and crafts blended African and European traditions in ways that still echo in Appalachian culture today—though too often without attribution.

Why The History of Freemen in Appalachia Was Buried

So why don’t we hear stories about Freemen in Appalachia in school?

The South’s postwar effort to rewrite its past is partly the answer. It was easier to present the Civil War as a tragedy between two white worlds than to reckon with free Black communities that didn’t fit either side’s mythology.

Another factor was the systemic loss of land and records. Many freed families lost their property to legal manipulation, taxes, or racial violence. Without land deeds or gravestones, their stories became ghosts.

And then there’s the myth of Appalachia itself—the idea that it was (and still is) an all-white, Scots-Irish enclave untouched by the racial complexity of the broader South. That myth persists in pop culture but has been challenged by modern research, evidenced by research into the Melungeons of Appalachia, a mixed-race group whose origins stretch back to colonial times.

A Slow Rediscovery

Fortunately, the silence is starting to break.

Historians, genealogists, and descendants are piecing together the past through census data, oral histories, church records, and archaeological findings. The Appalachian Trail Conservancy now marks the site of the Brown Mountain Creek community. Books and documentaries have begun to tell the stories that textbooks omitted.

Still, the work is just beginning. For every documented community, several more may be waiting to be rediscovered. And each one holds keys to understanding the Black experience and the broader American story.

The Legacy Lives On

The lost history of Freemen in Appalachia reminds us that freedom is rarely a finish line. It’s a negotiation—a day-by-day effort to live with dignity in a world that may not welcome you.

These were people who planted corn on hillsides, built churches from logs, raised children under threat of violence, and insisted on their right to exist. They shaped Appalachian history, even if their names were written out.

Their story isn’t just Black history. It’s American history. And now that we know it, we can’t look away.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.