John Chiswell Climbed into a Hole and Became a Legend

An installment in our Appalachian History and Culture series

Along a freeway passage where traffic travels north on I-81 while simultaneously going south on I-77 lies the exit for Ft. Chiswell, VA. One might expect to find some semblance of a colonial fort there, considering that Virginia is a state rich in historical sites. But there isn’t one. Instead, this crossroads hides its frontier past under a cloak of gas stations and convenience stores.

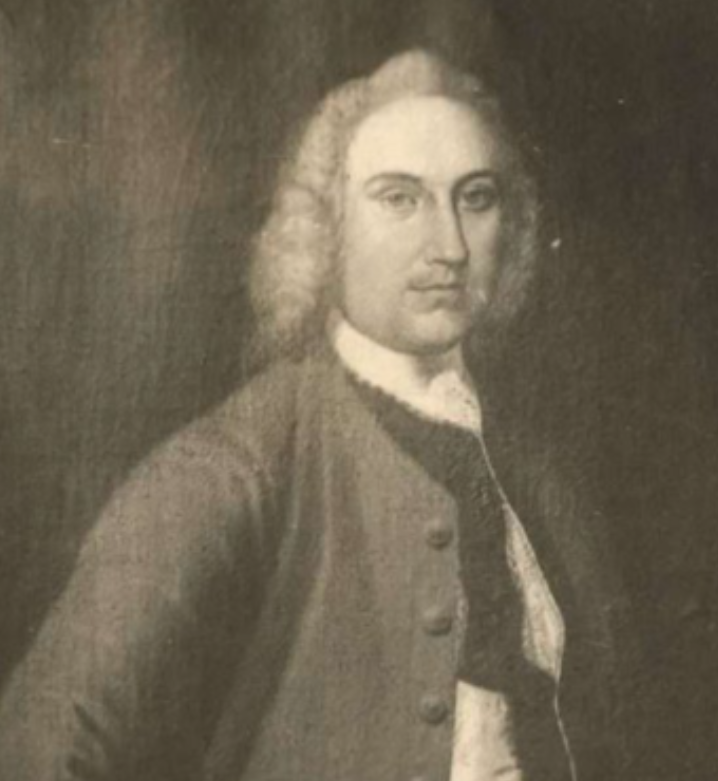

John Chiswell’s name is rarely heard in American history classrooms, so most people have no idea who he is. But to Southwest Virginians, he is the man who climbed into a hole and spawned an industry but suffered a scandalous death.

Chiswell’s Hole

The year is 1756. A young Englishman, John Chiswell, is deep in the wilderness of Virginia, his heart pounding in his chest. He is on the run, his breath ragged, his clothing damp with sweat. Behind him, Native Americans—likely Catawba or Cherokee—were in pursuit. He had stumbled into their territory and was running for his life.

Fear is sharp in his gut, but it also drives him forward. He pushes himself deeper into the woods as his pursuers grow closer. He spies a hole high on a rock face along the New River and climbs to the cave, seeking a hiding place.

Chiswell looks around. He is in a dark cavern, the air thick with an earthy smell. As his eyes adjust to the gloom, he sees something glinting in the faint light filtering through a crack above. Chiswell, a trained metallurgist, recognizes a lead/zinc ore vein in the dolomite rock. He is intrigued.

Chiswell sets about exploring the cave. He finds more veins of ore, richer and more extensive than he could have imagined. He emerges from the cave, blinking in the sunlight. The cries of his pursuers are faint now, lost in the distance. He has outrun them, not just physically but also figuratively. He has found his escape, his sanctuary.

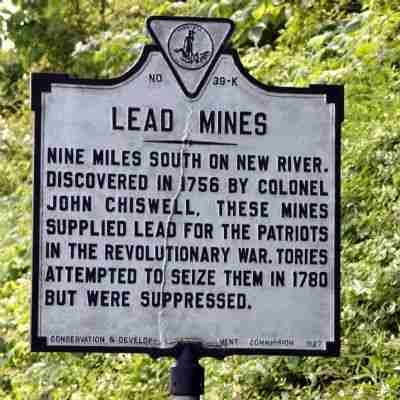

Chiswell secured the rights to the land and launched a mining operation that, over the decades, fostered economic development, brought the railroads to the Blue Ridge Mountains, and provided raw materials for the American Revolutionary War and the nascent nation. Austinville Lead and Zinc Mines produced one-third of all the lead and zinc in the American South.

Austinville—adjacent to Ft. Chiswell—became more than just a mine; it became a vibrant community with homes, shops, and churches. The mines survived until 1981, more than 200 years. Although the mines are gone, the community still thrives.

John Chiswell’s Demise

In his later years, Chiswell created a scandal that ended in his widely publicized death—possibly a suicide—the evening before his trial for the murder of a western Virginia merchant.

On June 3, 1766, Chiswell got into a drunken political argument with Robert Routledge at Mosby Tavern in Cumberland County, VA. Chiswell threatened Routledge with a candlestick and demanded that Mr. Routledge leave. When he refused, Chiswell stabbed him in the heart with his sword.

Chiswell was arrested, charged with murder, and jailed in Williamsburg. When he was allowed to post bail, the public was outraged. The justice who released him, William Byrd, was Chiswell’s business partner in the lead mining operation.

John Chiswell was found dead at his home in Williamsburg on October 14, 1766. It’s believed that he committed suicide, but that’s disputed. Because of the controversy surrounding his death, he was refused burial in the cemetery at Bruton Parish Church. He was instead buried in an unmarked grave at Scotchtown Plantation in Hanover County, VA.

The historical sites of Chiswell’s Hole and the Austinville Mines can be seen along the New River Trail State Park in Austinville, VA. For more information, visit the Friends of the New River Trail website.

More Appalachian History & Culture

Find more stories from the region’s past on the History and Culture page.

Appalachian History and Culture Collection

Enjoying Blue Ridge Tales? I hope so. If you’d like to help keep the site ad-free and the stories rolling, you can buy me a coffee.

To stay connected, subscribe to my Blue Ridge Tales newsletter, and have stories and updates delivered once a month to your inbox.