Loyalists, Lead Mines, and Lynch Law

An installment in our Appalachian History and Culture series

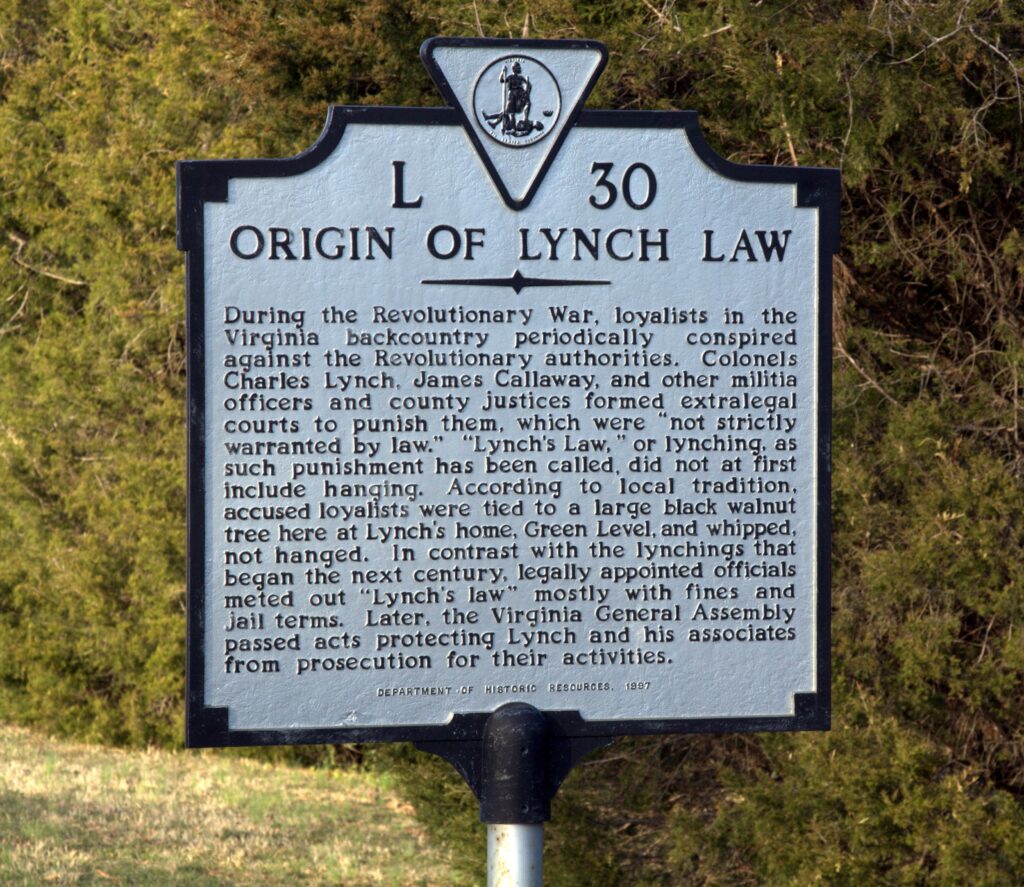

In the mountains of Virginia during the Revolution, justice didn’t always wait for courtrooms. Sometimes, it showed up with a rope and a warning. That’s how the phrase “lynch law” got started—right here in Southwest Virginia.

The lead mines near what’s now Wytheville were essential to the Patriot war effort. They produced the bullets. No lead, no firepower. That made the mines a target, and made folks loyal to King George and England a serious problem. So when rumors started spreading about a plot to sabotage the mines, a local colonel named Charles Lynch didn’t wait for a judge. He handled it himself.

The Threat to the Lead Mines

In 1780, Wythe County hadn’t been officially formed, but the lead mines were already a critical asset. They supplied shot for Continental troops up and down the frontier. Losing them would’ve been a blow the Patriots couldn’t afford.

At the same time, Loyalist sentiment in the region was rising. Some locals were tired of war. Some didn’t like the way the new government was forming. Others were just hoping to end up on the winning side—whichever one that was.

That mix led to real danger. There was talk of an uprising. Some claimed weapons were being stockpiled. Others said the Loyalists planned to attack the mines or hand them over to the British. Whether the conspiracy was fully formed or still in the planning stages didn’t matter. The Patriots weren’t going to take the risk.

Lynch Law Begins

Charles Lynch was a Patriot militia colonel and a landowner from Bedford County. He was also a justice of the peace, but when it came to the Loyalist threat, he didn’t bother with court procedures.

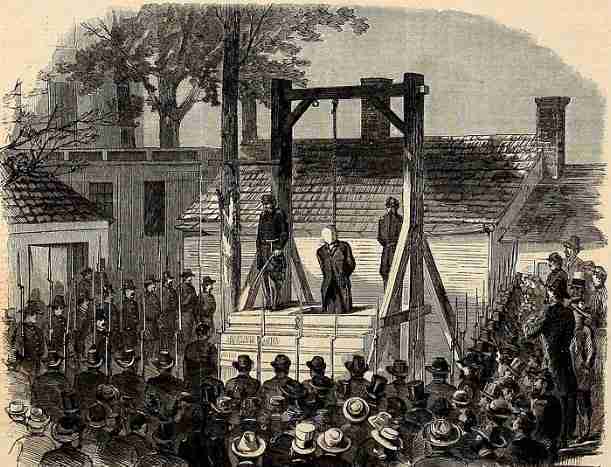

Instead, Lynch set up his own version of justice. He and his men rounded up suspected Loyalists—many from the New River region—and held what he called “summary trials.” These weren’t conducted in courtrooms. Some took place under trees, some on porches. Testimony was brief. Verdicts were quick. Punishments followed immediately.

Some were whipped. Some were conscripted into Patriot service. Others were forced to swear allegiance and pay fines. Lynch made it clear: if you were working against the Revolution, you’d answer for it. Fast.

It was improvised justice. And it worked, at least from the Patriot point of view. The plot fell apart, the mines stayed safe, and the region quieted down—for a while.

What “Lynch Law” Meant Back Then

The term “lynch law” first came into use around this time, referring to Lynch’s style of direct action. At the time, it was seen as practical. Even necessary. In the backcountry, where travel was hard and legal systems were slow, there wasn’t much patience for formalities.

Lynch’s methods weren’t without critics. Some questioned whether he had overstepped. Others worried that innocent men might have been punished on rumor alone. But in 1782, after the war’s tide had turned, the Virginia legislature passed a resolution protecting Lynch from prosecution. They recognized that what he’d done was outside the law, but considered it justified by the circumstances.

How the Term Changed

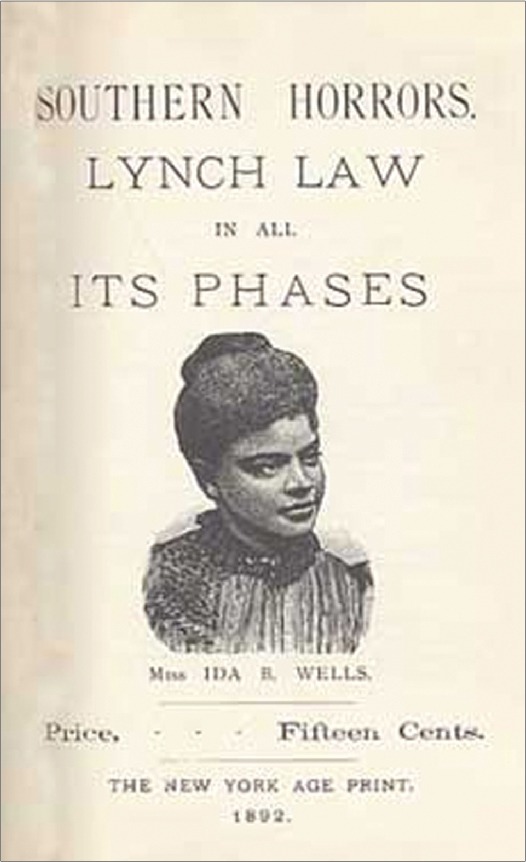

Over the decades, “lynch law” changed meanings. What began as a reference to swift Revolutionary justice evolved into something far more dangerous.

By the 1800s, the term was being used to describe extrajudicial violence—often mob-driven and often racially motivated. In the South, it became a cover for vigilante hangings, almost always without trial. And over time, “lynching” came to symbolize one of the darkest chapters in American history.

That shift in meaning wasn’t something Charles Lynch intended. But the name stuck. And what started as one man’s frontier justice became a national stain.

What Remains of It

Today, the lead mines are long closed. The towns have grown. The walnut tree where Lynch held his trials is gone. But the phrase “Loyalists, Lead Mines, and Lynch Law” still marks a turning point—a moment when fear met power and didn’t wait for permission.

It’s a story worth telling, not to glorify what was done, but to understand it. Lynch acted during wartime. He believed he was protecting his state and his neighbors. But what he set in motion had consequences far beyond his time.

We like to think justice is clean and fair. That there’s always time to weigh the facts. But in a crisis, when people feel threatened, the rules change. The problem is, once that door opens, it’s hard to close.

Lynch Law in Perspective

There’s no question that the lead mines were worth defending. And the Loyalist threat was real, even if the details were murky. Charles Lynch responded the only way he knew how—with fast decisions and hard outcomes.

But there’s a reason we have laws and procedures. They don’t just protect the accused—they protect the people doing the accusing from going too far.

Lynch’s name survived because his actions touched something deep in the American psyche: our discomfort with waiting. Our urge to fix things now. But justice, when rushed, doesn’t always land where it should.

That’s why the story of Loyalists, Lead Mines, and Lynch Law still matters. It reminds us how easy it is to trade process for speed, and how long we can live with the results.

The man himself had nothing to do with that turn. He died in 1796, likely unaware of how far the word would travel. But the seed he planted—improvised justice, outside the law—had taken root.

The Thin Line

So what do we do with this story of Loyalists, Lead Mines, and Lynch Law?

It’s tempting to sort history into neat piles: hero or villain, right or wrong. But Charles Lynch sits uneasily between them. He was trying to protect something fragile—an unformed country, bleeding from all sides. And he succeeded. The mines stood. The British never got their lead.

But in the process, he proved how easy it is for fear to erode justice—and how quickly a rope in one war becomes a weapon in the next.

The tree is gone. The mines are closed. But the questions remain: How do we balance safety and rights? Can we ever trust justice that skips the rules?

More Appalachian History & Culture

Find more stories from the region’s past on the History and Culture page.

Appalachian History and Culture Collection

Enjoying Blue Ridge Tales? I hope so. If you’d like to help keep the site ad-free and the stories rolling, you can buy me a coffee.

To stay connected, subscribe to my Blue Ridge Tales newsletter, and have stories and updates delivered once a month to your inbox.