Old Christmas in Appalachia: Celebrating Tradition

In the heart of Appalachia, when winter settles deep into the valleys and the mountains stand quiet under a blanket of frost, a different kind of Christmas takes place. While most of the world celebrates on December 25, some Appalachian communities hold on to a much older tradition. Old Christmas, celebrated on January 6. It’s a day steeped in history, superstition, and the unique spirit of a region that has long cherished its customs. But why, you might wonder, do some Appalachian families celebrate Christmas twice?

A Look Back: The Old Christmas Origin Story

The roots of Old Christmas stretch back to 1752, when England and its colonies switched from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar. The Julian calendar—named for Julius Caesar—was designed to correlate the spring equinox with calendar months. The calendar—consisting of 365 days—was used throughout the Roman Empire. But, as we know, solar years aren’t exactly 365 days long.

Over the next 1500 years, the calendar drifted significantly. Finally, in 1582, Pope Gregory XIII instituted a new calendar to realign with astronomical events, especially the spring equinox, which is central to determining the date of Easter in the Christian tradition.

In doing so, the calendar “lost” eleven days, meaning Christmas was suddenly celebrated earlier, on December 25. While most Catholic countries adapted to the change, Protestant countries—including England and its former colonies—continued to observe Christmas on its original date, January 6. This date became known as Old Christmas, a tradition that remained alive in the region for centuries, especially in Appalachia.

In these remote mountain communities, isolation wasn’t just a geographical reality—it also allowed older European traditions to survive in ways they didn’t elsewhere. For the people of Appalachia, Old Christmas wasn’t just about keeping a date on the calendar; it came with its unique set of beliefs and customs that made it distinct.

A Night of Superstition and Quiet Wonder

One of the most intriguing aspects of Old Christmas in Appalachia is the rich layer of superstition that accompanies the celebration. Folklore claimed that at midnight on Old Christmas Eve, animals in the barn would kneel and speak, recognizing the birth of Christ. It’s said that you could hear the cattle low softly in prayer if you were still enough to listen.

But people were told not to disturb the animals during this sacred hour. This wasn’t a time for human eyes; it was a holy moment between the creatures and the divine. This blend of religious reverence and folk belief made perfect sense in a region where farming and livestock were a way of life.

Other superstitions floated around as well. Bees were said to hum in their hives, marking the night’s significance. The air was thick with a sense of magic, and families might sit quietly by the fire, reflecting on the mysteries outside their windows.

Breaking Up Christmas: The Appalachian Twist

If Old Christmas Eve was a time of quiet reflection, the days leading up to January 6 were anything but. Enter the tradition of Breaking Up Christmas, where the twelve days between December 25 and Old Christmas were filled with parties, music, and lively gatherings. In Appalachia, people weren’t in a hurry to take down their decorations or finish their celebrations—Christmas wasn’t over yet.

Neighbors would host gatherings that often stretched late into the night, with fiddle and banjo music filling the air. These weren’t formal events; people would move from house to house, bringing their instruments and good cheer. It was a time for dancing, singing, and sharing food—keeping the holiday spirit alive long after the rest of the country had packed away the tinsel.

The music, in particular, played a central role in Breaking Up Christmas. Old-time Appalachian tunes set the rhythm for these gatherings, with each home offering a slightly different version of the same songs. And in a place where music has always been at the heart of community life, these informal jams were as much a part of Christmas as the feast on the table.

Mumming: A Tradition of Mischief and Fun

Another, more mischievous tradition during the Old Christmas season was mumming. Mummers were groups of costumed neighbors who would disguise themselves and visit homes, performing short skits, telling jokes, or singing songs in exchange for food or drink. The costumes were often simple—ragged clothes or masks—but the fun was in the disguise and the surprise.

Mumming added a layer of humor and excitement to the season. It wasn’t just about the performance; it was about upending the everyday roles people played. A quiet neighbor might suddenly become the most boisterous character of the night, and for once, everyone could let loose. In some ways, it echoed the same playful spirit as the “Lord of Misrule” traditions found in Old World Christmases, where the normal social order was turned on its head for a day. The mumming tradition carries on today. Its most spectacular representation is the annual Mummer’s Parade in Philadelphia.

Old Christmas Today: A Quiet Echo

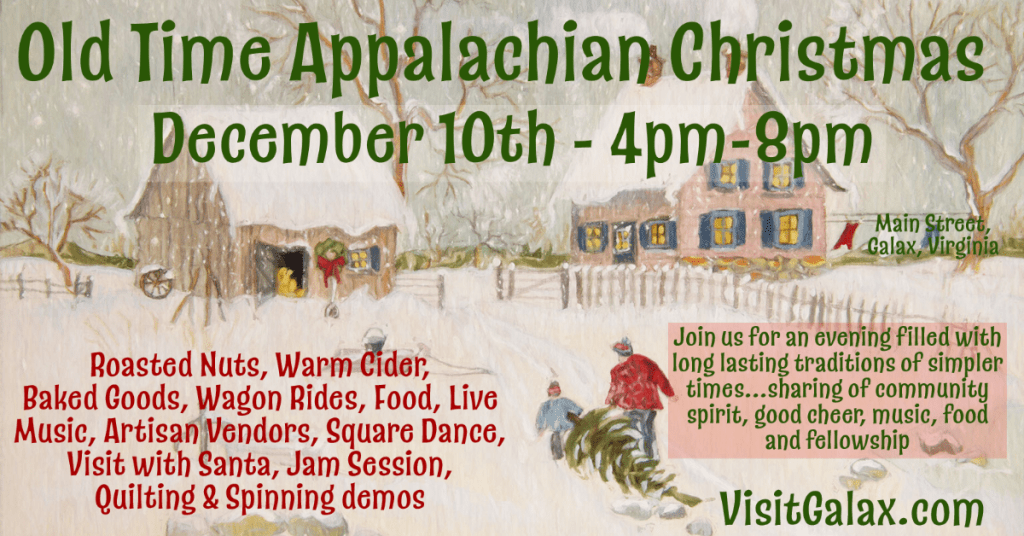

Though Old Christmas isn’t as widely celebrated as it once was, the tradition survives in pockets of Appalachia, where families and communities continue to gather on January 6. In places like western North Carolina and parts of Virginia, small gatherings and musical events still honor the old ways. The superstitions might not be as strictly observed, but the day holds a special significance for those who have kept the tradition alive.

Some families celebrate by holding simple meals, lighting candles, or sharing stories about the history of Old Christmas. It’s less about the rituals themselves and more about maintaining a connection to the past, a reminder that the season of Christmas once stretched beyond the modern calendar’s limits.

For many, it’s a time to pause after the rush of December to reflect on the quiet beauty of winter and the holiday’s deeper meaning. After all, in a region where the rhythms of the land once governed life, it makes sense that Christmas would be a season, not just a day.

The Enduring Spirit of Old Christmas

As the mountains of Appalachia stand quiet under the January sky, the spirit of Old Christmas endures. It’s a quieter kind of celebration that still carries weight. It reminds us that Christmas doesn’t have to end when the gifts are unwrapped—it can linger softly in how we gather with our loved ones, in the songs we sing, and in the traditions we keep alive. In the end, Old Christmas reflects what the season is truly about: community, connection, and the joy of keeping the lights burning just a little longer.

Comments are closed.