The American Chestnut: Fall and Salvation

An installment in our Appalachian History and Culture series

When European settlers came to the Blue Ridge Mountains, one of every four trees in the forest was an American Chestnut. This giant stood tall amidst the lush greenery of the Blue Ridge, its wood and sweet nuts a boon for both wildlife and humans.

From mice, squirrels, turkey, deer, and bears to people and livestock, the bountiful yields of the American chestnut were a reliable food source. Pioneers used its strong, straight-grained wood to build homes, furniture, and fences. The tree’s towering trunks, and the sight of its summer blossoms were a testament to its vitality and abundance.

But this once-emblematic symbol of Appalachian landscapes endured a disastrous blight in the 20th century. Nonetheless, it stands today as a symbol of resilience and hope, with extensive efforts being made to restore its reign.

The Chestnut Blight: An Unseen Enemy

Around the turn of the 20th century, the chestnut’s flourishing era abruptly stopped. A foreign fungus, borne on the wind and carried by humans across the lands, marked the start of the chestnut’s downfall. Manifesting as an orange fungus on the tree’s bark, this was the precursor of the chestnut blight.

The blight, traveling at a rate of 30-50 miles per year, left a trail of dying chestnut trees in its wake. By the 1950s, an estimated 4 billion trees across the East were lost, a catastrophe that deeply scarred the Appalachian landscapes.

The American Chestnut Fights for Survival

In the face of this environmental crisis, The American Chestnut Foundation (TACF) emerged to restore hope. Since its inception in 1983, the foundation has worked tirelessly to restore the American chestnut to its native habitat.

TACF embarked on a mission to breed the blight-vulnerable American chestnut with its Chinese counterpart known for its blight resistance. This led to the creation of a hybrid that was 15/16 American, preserving the tree’s inherent characteristics while enhancing its blight resistance.

Reclaiming the Mine Sites

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, large tracts of forested land were clear-cut and strip-mined. Hillsides were washed away, and streams were polluted by the runoff. Attempts were made to slow mountainside erosion, most notably by introducing the Japanese plant kudzu. But kudzu’s rapid growth allowed it to smother native trees, shrubs, and other plants. It blocked sunlight, preventing photosynthesis and eventually killing those plants.

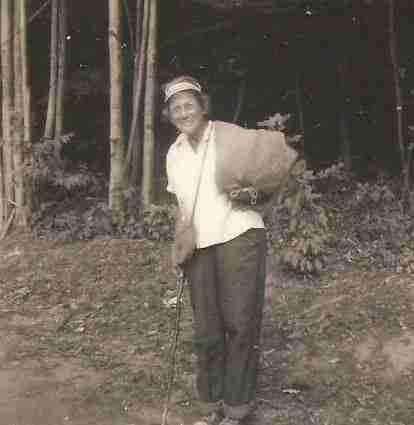

In an innovative effort to restore the chestnut and reforest mined sites, TACF started planting hybrid chestnuts on reclaimed mine sites. This approach not only helped bring back the chestnut to its native landscapes but also aided in the reforestation of mine sites, a legal obligation for mining companies.

A Future Revival

Today, the chestnuts planted on these former mine sites and elsewhere offer hope for the American chestnut’s future. However, the success of these efforts won’t be certain for generations. We can be sure the restoration efforts have succeeded only when the chestnuts are back in the forest reproducing.

Despite the long road ahead, the dedication of foundations, researchers, and volunteers brings us closer to the day when the American chestnut will be restored to its former glory. The journey of the American chestnut, from its golden era to its downfall and now its potential revival, stands as a testament to nature’s resilience and the power of persistent human effort.

More Appalachian History & Culture

Find more stories from the region’s past on the History and Culture page.

Appalachian History and Culture Collection

Enjoying Blue Ridge Tales? I hope so. If you’d like to help keep the site ad-free and the stories rolling, you can buy me a coffee.

To stay connected, subscribe to my Blue Ridge Tales newsletter, and have stories and updates delivered once a month to your inbox.