The Price of a View: Human Cost of the Blue Ridge Parkway

An installment in our Blue Ridge Travel series.

We all say the same thing the first time we see the Blue Ridge Parkway: “The view is incredible.”

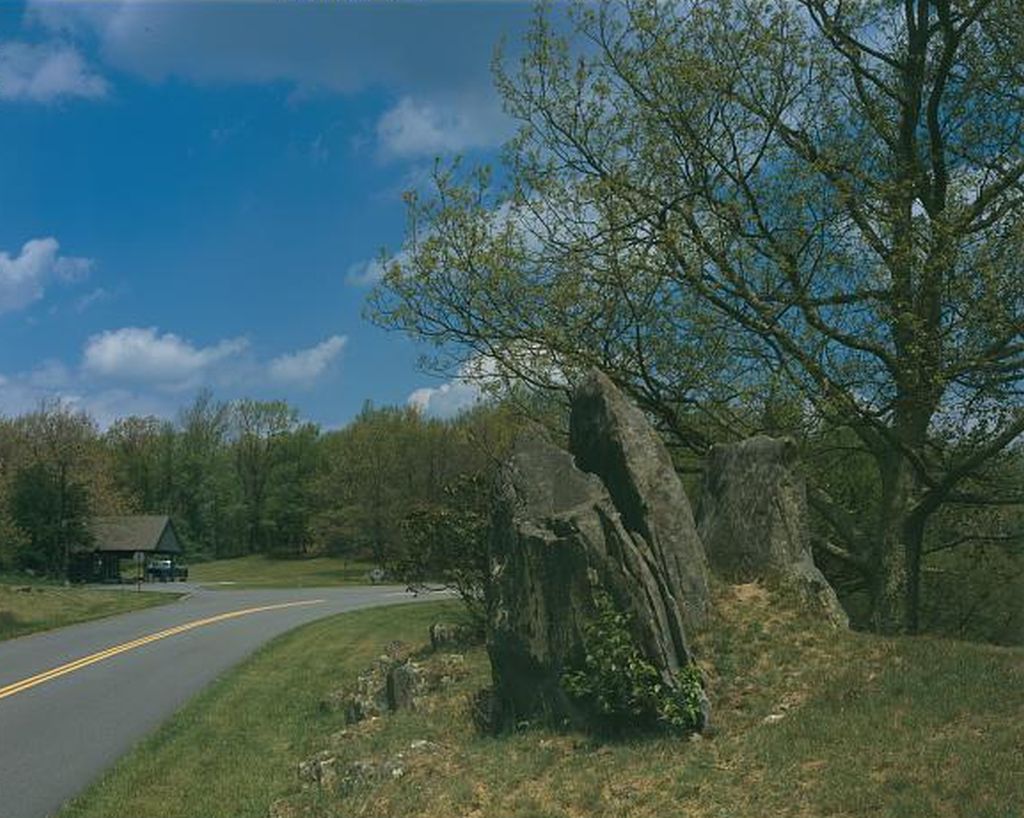

The Blue Ridge Parkway, with its winding curves and postcard overlooks, offers some of the most stunning scenery in the eastern U.S. It’s the kind of road that makes you slow down, roll down the windows, and breathe a little deeper.

But here’s what the brochures don’t tell you.

Before there was a view, there was a home.

Before the quiet, there was a community.

And before the Parkway, there were people who lived on that land.

A Dream Cut into the Mountain

In the 1930s, as the country staggered through the Great Depression, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal promised relief through big ideas—dams, parks, and highways. One of those projects was a scenic road to link Shenandoah National Park in Virginia to the Great Smoky Mountains in North Carolina. It would be called the Blue Ridge Parkway, and it would stretch 469 miles across the spine of the Appalachians.

The idea wasn’t just about transportation—it was about inspiration. A road that followed the natural contours of the land. No billboards, no fast food signs. Just curves, flowers, and views to stir the soul.

But here’s the catch: the government needed land to build that kind of road.

And a lot of that land was already spoken for.

When the Government Comes Calling

In some areas, the Blue Ridge Parkway ran through a national forest. That was the easy part. But across the Shenandoah Valley and the Virginia foothills, it cut through private farms, family homesteads, and entire communities that had been around since long before the idea of a national park was born.

The government used a process called eminent domain, giving people a price for their land and telling them to move. On paper, it was fair compensation. In reality, it often wasn’t fair, and people had no choice.

Some older residents were offered “life leases”—they could stay until they died but with restrictions. No remodeling. No leaving the place to their kids. No planting too close to the road if it messed with the view.

Others didn’t even get that. They packed up, left their homes behind, and watched as bulldozers turned apple orchards and family cemeteries into scenic overlooks.

All so we could take prettier pictures.

The Stories That Got Paved Over

The history books have plenty to say about the Blue Ridge Parkway’s construction—government reports, design plans, and photos of CCC crews carving switchbacks into the hills. But what are the stories of the people who were displaced? Those mostly survive in family scrapbooks, local archives, and fading memories.

In places like Love, Virginia—yes, that’s really the name—entire ridgeline communities were uprooted. Families who’d lived on the same land for generations ended up in the valleys, away from their churches, their gardens, and the graves of their kin. Most never returned. Some didn’t even talk about it again.

And those life leases? They weren’t always peaceful. In Botetourt County, an elderly couple was warned by park rangers not to grow vegetables too close to the road. It wasn’t “scenic” enough.

That’s what it came down to: if your barn, smokehouse, or sagging porch didn’t match the government’s idea of rustic charm, it had to go.

A Landscape Curated for Tourists

The Blue Ridge Parkway was meant to show off an “ideal” version of mountain life. Something wild but tidy. Remote but safe. A little rustic, but not too real.

So the messy parts—the woodpiles, laundry lines, and hand-dug wells—got scrubbed out of the picture. In some cases, a cabin might be preserved if it could serve as an “exhibit,” like the Brinegar Cabin in North Carolina. But the real families living in similar cabins? They were relocated, and their homes torn down.

What we’re left with is a kind of curated emptiness. A beautiful silence that sometimes feels just a little too quiet.

What Gets Left Behind

Losing a home isn’t just about geography. It’s about memory. It’s about place.

It’s where your grandfather split logs every fall. Where your mother stirred beans on a woodstove. Where your sister got married under a stand of dogwoods.

When you lose that, something deeper than property changes. You lose the anchor.

Some families tried to go back to visit what used to be. Others closed the door on the past. Their children grew up without knowing where the orchard had been or why Grandma got quiet when someone mentioned the Parkway.

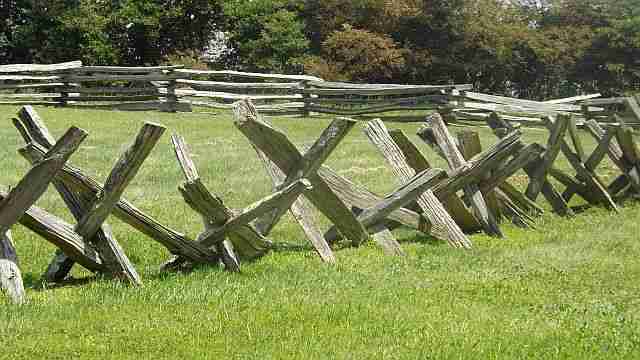

But if you wander just off the road—past the rhododendrons and into the brush—you can still find traces. A mossy stone wall. A root cellar, sunken into the earth. Fence posts leaning like old men. And sometimes, a family graveyard with names no signpost ever mentions.

What We Owe the View

None of this is to say the Parkway shouldn’t have been built.

It gave people jobs during hard times. It preserved swaths of wilderness that might’ve been bulldozed for shopping centers or ski resorts. It has brought joy and peace to millions.

But it also took something.

The people who lived here before the road are not in the brochures. Their houses aren’t on the maps. Their names aren’t carved into the overlook signs.

And maybe that’s something we should change.

Today, scholars and local historians are trying to recover those voices—digitizing records, collecting oral histories, and piecing together who lived where, and why it mattered.

But we don’t have to wait for a museum plaque.

Next time you stop at a Parkway overlook, don’t just look out at the valley. Step off the pavement. Listen a moment. Imagine the swing creaking on a front porch that isn’t there anymore. Picture the garden rows, the apple trees, the smoke curling from a chimney.

And then ask yourself: Who paid for this view?

Because beauty without memory isn’t heritage—it’s just scenery.

And we owe more than that.

More Blue Ridge Travel

Find more travel stories, routes, and small-town stops on the Blue Ridge Travel page.

View the Blue Ridge Travel Collection here

Enjoying Blue Ridge Tales? I hope so. If you’d like to help keep the site ad-free and the stories rolling, you can buy me a coffee.

To stay connected, subscribe to my Blue Ridge Tales newsletter, and have stories and updates delivered once a month to your inbox.