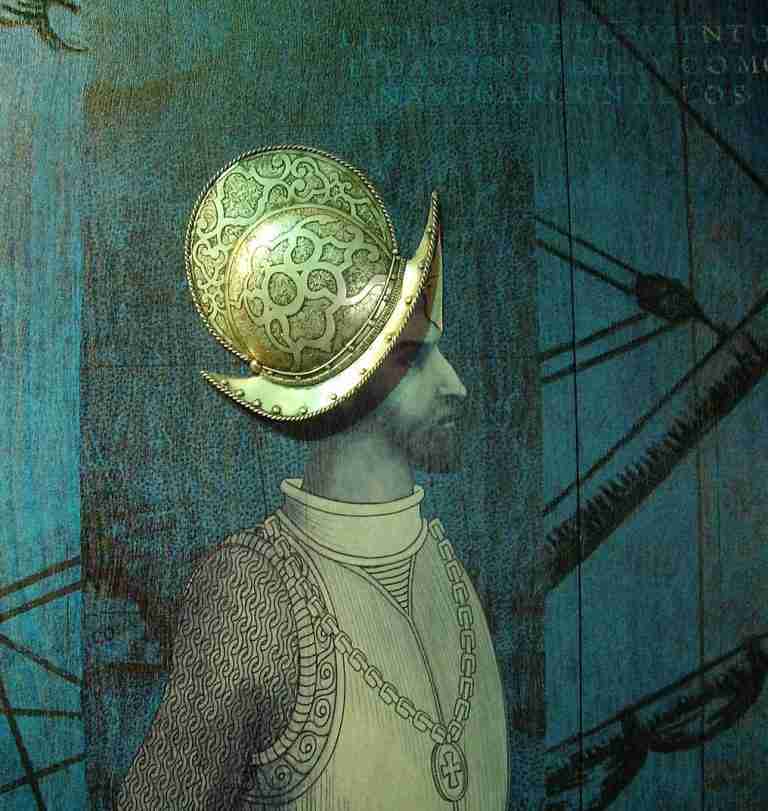

They Never Left: Cherokee in Appalachia

An installment in our Appalachian History and Culture series

We’re taught the Trail of Tears as an ending—a final march west, away from ancestral homelands. But what if it wasn’t the end? What if some never left?

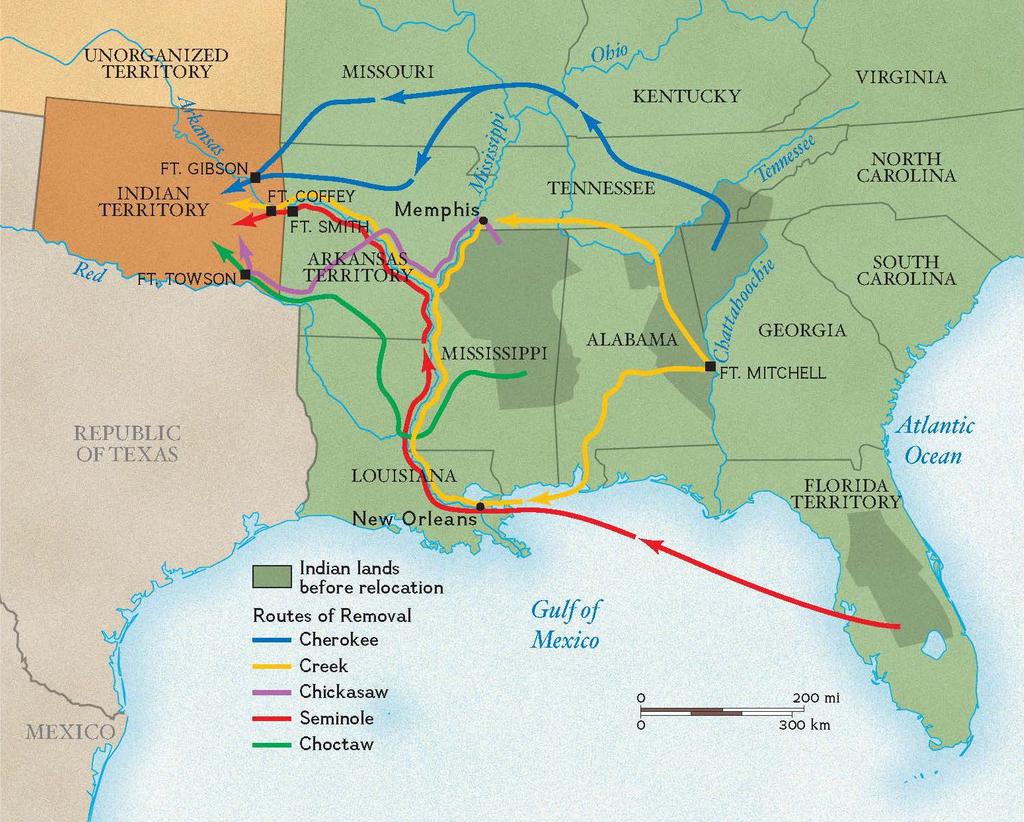

In 1838, under orders from the federal government, thousands of Cherokee men, women, and children were rounded up at gunpoint and forced to march nearly 1,000 miles to Indian Territory. Thousands died along the way. The removal is remembered as one of the darkest chapters in American history. What’s less remembered is that not all the Cherokee in Appalachia were removed.

Some stayed. Some resisted—not with weapons, but with strategy, endurance, and deep ties to their land. This isn’t a story of mythic rebellion. It’s a story of quiet refusal, of cultural survival in the face of state-sponsored erasure. And it happened right here in the mountains of Appalachia.

The Official Story vs. the Lived Reality

The U.S. government intended for the removal to be total. The 1835 Treaty of New Echota, signed by a minority faction of Cherokee in Appalachia, gave the appearance of legality to a forced expulsion already in motion. When removal began in earnest in 1838, federal soldiers and state militias moved through the Appalachian foothills and valleys, capturing Cherokee families and herding them into internment camps.

But the Blue Ridge Mountains don’t easily yield their people.

While the official goal was total removal, in practice, geography, alliances, and timing opened cracks in the system. Some Cherokee in Appalachia were simply never captured. Others had already lived on lands not easily accessed by federal troops. And a small number had acquired land titles or legal standing—often through years of negotiation, political alliance, or assistance from white advocates.

The result: several hundred Cherokee remained in their homeland. They didn’t “escape” removal—they endured it differently.

Staying Put: The Many Forms of Resistance

Remaining in the Southern Appalachians after 1838 was neither simple nor safe. It took preparation, support, and extraordinary resilience.

Some families were never reached by removal parties at all. They lived in remote hollers, far from roads or settlements, where soldiers weren’t inclined to search. Others fled into the highlands when word spread that the roundups had begun. This wasn’t easy evasion—it was deliberate withdrawal into the hardest-to-reach corners of the land their families had lived on for generations.

Many were helped by neighbors—particularly white allies who were sympathetic or indebted to them, and in some cases, by free Black families who shared land and hardship. Some Cherokee in Appalachia had long maintained ties to these communities through trade, labor, or intermarriage, and those relationships became critical for shelter and supplies.

But hiding wasn’t a long-term solution. Survival meant reestablishing stability. A few individuals had previously acquired private land holdings in their own names—or had relationships with white intermediaries who helped secure legal deeds in the names of spouses, children, or trustees. These holdings offered a legal foothold in the very land being emptied.

In some areas, families were constantly threatened to be discovered or reclassified as “unauthorized” residents. Others quietly tolerated their presence, especially when local economies depended on their labor, trade, or agricultural expertise.

There was no single strategy. There was no unified plan. But each act of staying—each decision to resist removal in place—was its own kind of protest. Not loud, not romanticized. Just a refusal to be erased.

The Foundation of the Eastern Band

In the decades that followed, those scattered families began to reconnect. The survival of these Cherokee communities gave rise to what is now known as the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, headquartered in Western North Carolina.

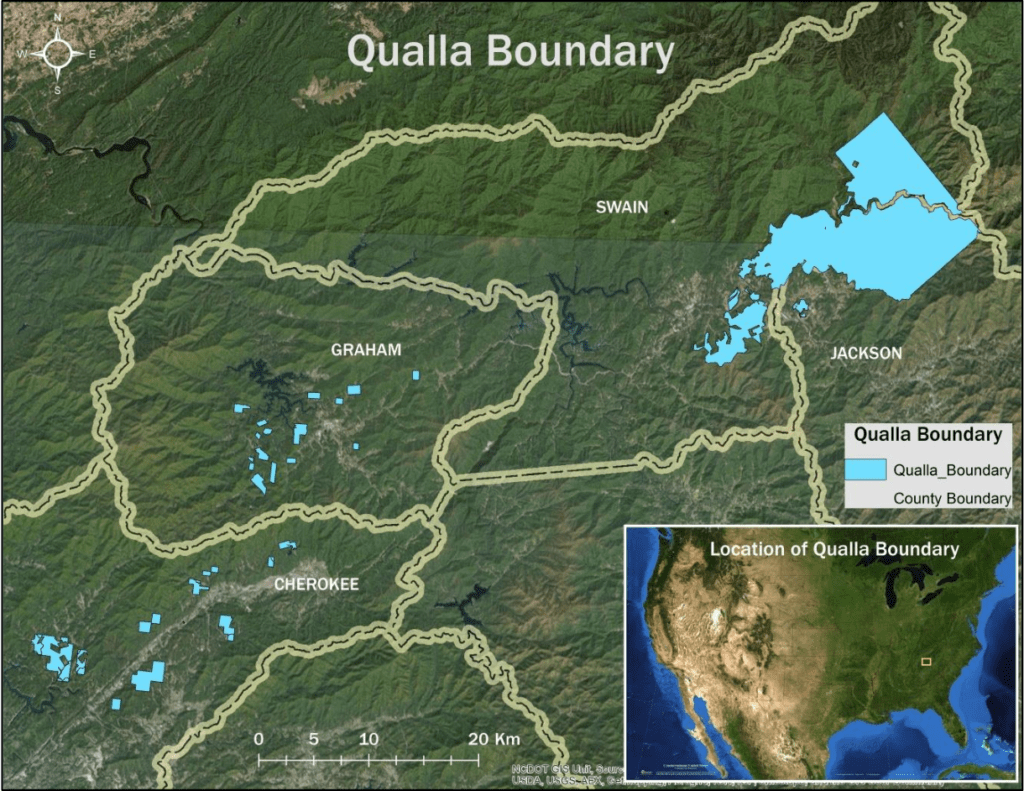

Their home base—the Qualla Boundary—wasn’t a reservation granted by the U.S. government. It was land purchased, parcel by parcel, beginning in the 1840s. Much of this effort was led by William Holland Thomas, a white man who had grown up among the Cherokee and was adopted by a chief. Because Cherokee citizens could not legally buy land then, Thomas used his status to purchase acreage on their behalf.

But make no mistake: the Eastern Band of Cherokee in Appalachia didn’t reappear—they never left. Their recognition as a distinct, sovereign tribal nation would come much later. In the meantime, they lived in a legal gray zone, holding onto language, culture, and memory in the margins of a country that had tried to erase them.

Continuity in the Mountains

Today, the legacy of that resistance lives on.

The Qualla Boundary isn’t just a place—it’s a living testament to survival. The Cherokee language is still spoken and taught in immersion schools. Ceremonial practices, dances, and oral histories continue in public and private spaces. Sacred sites like Kituwah, considered the Cherokee mother town, are still visited, honored, and protected.

The mountains themselves carry this memory. Trails now used by tourists and hikers once carried Cherokee traders and messengers. The place names—Oconaluftee, Nantahala, Tuckasegee—aren’t echoes of the past, but continued presence in a landscape that remembers who came first.

Of course, survival hasn’t meant ease. The Eastern Band faces ongoing challenges: economic pressure from tourism, the complicated legacies of boarding schools, the struggle to preserve language in a digital age, and federal policies that remain inconsistent. But their presence isn’t symbolic. It is real, active, and rooted.

A Legacy That Reshapes the Story

To say “they never left” isn’t just to correct a historical oversight. It’s to rethink what resistance looks like.

Too often, survival is overlooked because it doesn’t match our expectations of heroism. But in the case of the Cherokee who remained in Appalachia, resistance was shaped by endurance. It was quiet but deliberate. It looked like planting crops in familiar soil while soldiers marched others west. It looked like preserving ceremony in private while the law erased your name. It looked like staying.

The Trail of Tears was designed to make the Cherokee in Appalachia a people of the past. But they are not. They are here—in classrooms, on councils, in churches and forests and powwows. The people who stayed made that possible. Not by luck. Not by myth. But by knowing who they were and refusing to let the mountains forget it.

More Appalachian History & Culture

Find more stories from the region’s past on the History and Culture page.

Appalachian History and Culture Collection

Enjoying Blue Ridge Tales? I hope so. If you’d like to help keep the site ad-free and the stories rolling, you can buy me a coffee.

To stay connected, subscribe to my Blue Ridge Tales newsletter, and have stories and updates delivered once a month to your inbox.