Tinsmith to Tourist: A Vanishing Appalachian Trade

An installment in our Appalachian History and Culture series

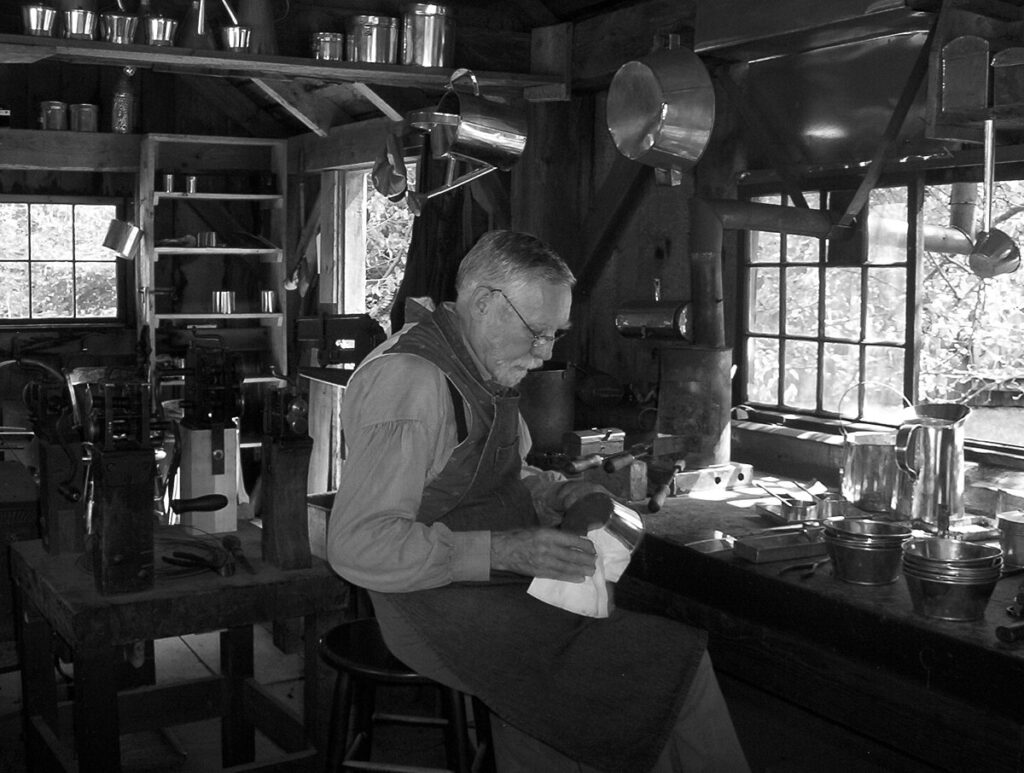

You could hear the shop before you saw it. A steady rhythm of clinks and taps echoed from the open door—tin snips biting into metal, hammers flattening seams, the soft hiss of solder melting into a joint. Inside, the tinsmith bent over a worn bench lit by lamplight, sleeves rolled up, hands blackened with soot.

Today, there’s no sound at all. The shop is gone. A vape store’s moved in where the tin once shined. Same footprint. Different fire.

In most Appalachian towns, that’s how old trades disappear—not with ceremony, but with silence. One day you’re buying a funnel. Next week, you’re buying flavored fog.

The Trade That Lit the Mountains

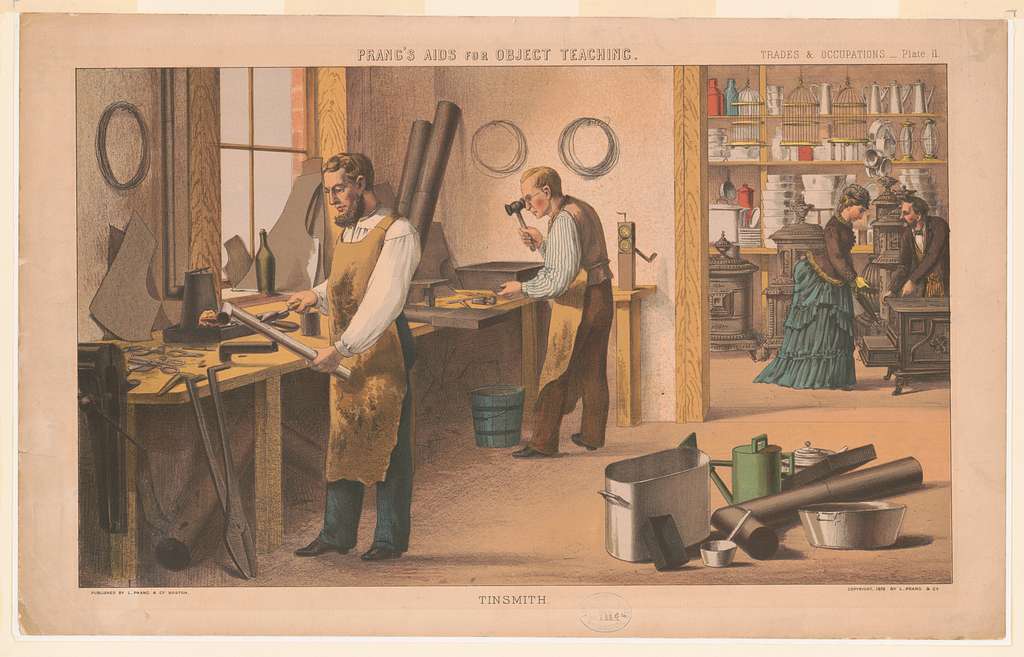

Tinsmiths once made the mountains work. From stovepipes to lanterns, roofing shingles to flour scoops, the tinsmith kept homes sealed, fires lit, and kitchens functional. Tin was lightweight, cheap, and pliable—a working man’s metal.

In the Blue Ridge, a tinsmith’s shop might share space with a general store or blacksmith. He shaped tinplate with snips, curled edges on a stake anvil, soldered joints with rosin and flame. Sometimes he crafted decorative pieces—weather vanes, candle molds, punched lanterns with patterns of stars and hearts.

His was a quiet kind of making: one that valued utility over beauty. But the things he made lasted—until they didn’t.

When the Factories Came

The decline didn’t happen all at once. By the late 1800s, factory-made goods from Baltimore, Philadelphia, and even overseas were crowding the store shelves. Why buy a handmade dipper when Sears offered a dozen for the same price?

By the 1940s, local tinsmiths had become scarce. A few clung to the trade, working part-time, patching gutters or repairing roofing. Some shifted into hardware sales. Others just shuttered their shops.

In time, even the memory faded. A generation came and went without hearing the clang of a mallet or the rasp of a file on tin. The last of the bench stakes were sold at auctions, boxed up as “vintage tools.

Sidebar: Tinsmith or Tinker? What’s the Difference?

The words “tinsmith” and “tinker” are often used interchangeably—but in Appalachian life, they weren’t quite the same.

Tinsmiths were settled artisans. They worked from home shops or general stores, shaping tinplate into lanterns, candle molds, roofing panels, dippers, or stovepipes. Their work was precise, essential, and often custom-made. A good tinsmith was part of the town’s rhythm—firing up his soldering pot alongside the blacksmith, turning out goods for neighbors and merchants alike.

Tinkers, on the other hand, traveled. They roamed the hills with soldering irons and toolboxes, going door to door to mend cracked kettles, patch holes in wash tubs, or fix warped lids. A tinker rarely made new goods—he kept old ones alive. In some communities, tinkers were welcomed; in others, viewed with a touch of suspicion, as outsiders passing through.

In truth, many mountain craftsmen wore both hats. A man might build tinware all winter, then sling a repair kit over his shoulder and hit the road when the snow melted.

One made the goods. The other kept them going. And in a place where nothing was thrown away lightly, there was room—and respect—for both.

Heritage as Hobby

You can still find a tinsmith in Appalachia—just not where you used to.

At heritage festivals and craft fairs, a few reenactors keep the trade alive. They dress the part, work the old tools, explain the difference between tinplate and galvanized sheet. Some even teach short workshops on how to shape and solder.

But it’s performance now, not profession. These makers aren’t outfitting cabins—they’re outfitting booths. Their work is valued, but not needed.

At a Heritage Festival in Abingdon, VA, a man tapped out the pattern for a punched-tin lantern while a child stared, wide-eyed. “What is he doing?” she asked her mother. The answer—“He’s making something”—felt more historic than the act itself.

What’s Lost When a Trade Fades

The tinsmith didn’t just make things. He represented a way of life—one where things were built to last, repaired when broken, passed down instead of thrown away.

That mindset still lingers in some mountain homes, where soldered pails hang on porch walls, or where old oil lamps gather dust on the mantel. But the people who made them—those who could look at a flat sheet of tin and see a shovel scoop or chimney cap—are mostly gone.

One local auctioneer said it best: “We’ve got more people selling antique tools than folks who know how to use them.”

A Final Trace

You might not notice it at first. It blends into the background—like ambient music in a Walmart. But if you’ve ever been in a barn loft or root cellar and found a square of tin bent into a patch, fastened with hand-cut nails and sealed with pine pitch, you’ve touched more than a fix. You’ve touched a moment when someone believed in repair. Believed that work could be both practical and precise. Believed that a thing, made well, ought to last.

There’s a kind of reverence in those objects—not because they’re rare, but because they were never meant to be noticed. Just used. Just useful. Until they weren’t needed anymore.

The last Appalachian tinsmith didn’t get a retirement party. No newspaper profile. No plaque. Just a final job—maybe a flue cap, maybe a feed scoop—and then a quiet locking of the shop door.

What Remains

In the end, the tinsmith’s trail didn’t vanish. It just narrowed.

It leads now through museum exhibits and dusty toolboxes. Through the hands of heritage workers and weekend crafters. Through families who still keep the coal stove lit on Christmas morning because “that’s how Granddad did it.” Through a lantern hanging in a shed that still gives off light—tarnished but working, with a little solder holding strong.

The trail may be faint. But if you know where to look—and what you’re looking for—it’s still there.

Still shining.

Just like tin.

More Appalachian History & Culture

Find more stories from the region’s past on the History and Culture page.

Appalachian History and Culture Collection

Enjoying Blue Ridge Tales? I hope so. If you’d like to help keep the site ad-free and the stories rolling, you can buy me a coffee.

To stay connected, subscribe to my Blue Ridge Tales newsletter, and have stories and updates delivered once a month to your inbox.