Tobacco Bag Stringing: Craft, Culture, and Survival

Amid the harsh economic strains of the Great Depression, the unassuming craft of tobacco bag stringing emerged as a lifeline for many Blue Ridge families. This craft involved the simple—but tedious—task of threading drawstrings into tobacco bags. These bags held more than tobacco; they promised survival and a speck of prosperity for those who stitched their way through hard times.

One Billion Bags a Year

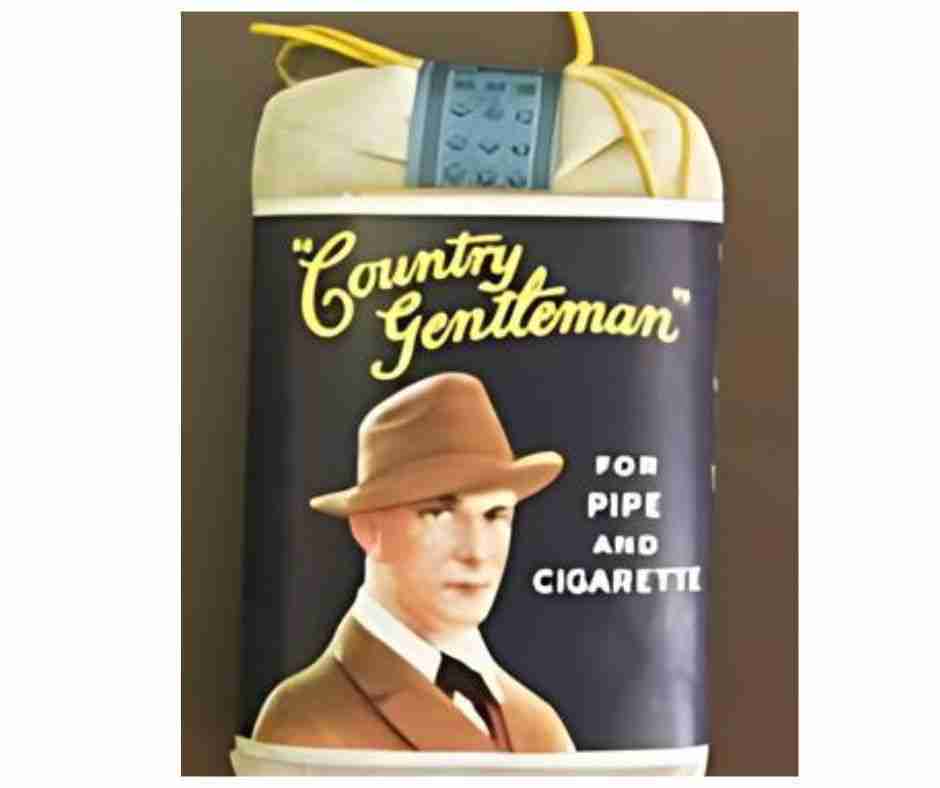

During the Great Depression, the tobacco-growing regions of North Carolina and Virginia buzzed with activity. At a time when cigarette smoking was commonplace for nearly 80% of American men, the demand for loose tobacco was huge. To save money, many smokers began to “roll their own.” A bag of loose tobacco—enough to roll about thirty cigarettes—cost just a dime, compared to fifteen cents for a pack of twenty machine-rolled cigarettes, making the craft of tobacco bag stringing an economic lifeline during hard times.

By 1939, three major companies dominated the tobacco bag market in the United States. Of these, only one had developed a method to insert drawstrings mechanically. The other two relied on manual labor for the task. Together, these three companies produced a staggering one billion tobacco bags a year.

What is Tobacco Bag Stringing?

The process involved threading drawstrings into small cotton or muslin tobacco bags, typically about four by three inches in size. Home workers received the bags pre-stitched on three sides, leaving an opening at the top. Stringers would thread a drawstring through each side, allowing the bag to be easily opened and securely closed. Some stringers became so proficient they could string up to a thousand bags daily, earning around fifty cents for their efforts.

The Art of Survival

Keep in mind that during the Depression, work was scarce, and wages were low. The average worker wage in cities was about $17/week, bottoming out at around $7. Even doctors earned only about $60/week. In Appalachia, jobs were nearly nonexistent. Railroads, logging, mining, and New Deal work projects (like building the Blue Ridge Parkway) continued to offer employment. Still, many mountain folk relied on subsistence farming. Cottage industries—like bag stringing—provided some much-needed cash.

Work distribution often came through a “bag agent,” a role usually filled by local businessmen or county officials well-acquainted with the community. These agents were crucial, especially when the demand for bags from home workers exceeded the supply of bags. A bag agent in Leaksville, N.C., in 1939, described his ongoing challenges in distributing bags when demand was high from residents desperate for work:

“…Every day, I have hundreds of requests for bags above that I am able to provide. They come at me from every angle, telephone, doorbell. Since my business is in my residence, they’ll even go around the house and come in the back door just to tell me how needy they are and ask me to please get them some bags to string to help out in the little they now receive.”

A Day in the Life of a Bag Stringer

The task of tobacco bag stringing became a daily routine for many. While men worked jobs or their land, women and children often took to stringing bags. Gathered around piles of tobacco bags, they’d spend hours threading drawstrings. The task, while tedious, was approached with dedication. The income bought flour, coal, soap, salt, shoes, and other necessities they would otherwise do without. Each drawstring pulled meant a step away from want, a minor victory in their daily struggle. The repetitive motion of stringing, the sound of the radio, and the murmur of voices became the soundtrack of their survival. The task was simple but held profound significance as a lifeline in desperate times.

Threads of Hope

Tracing the paths of those who lived through the Great Depression, their resilience and adaptability are impressive. Tobacco bag stringing was more than just a way to earn money; it was a testament to the spirit of householders determined to survive. Each bag strung, each day spent in the quiet labor of survival, was a stitch in the fabric of their collective history.

Reflecting on the emotional weight these simple bags carried, I’m reminded of the strength of unity and the quiet dignity of hard work. In remembering their story, we honor the spirit of those who, with nimble fingers and steadfast hearts, wove together the threads of their lives in the face of adversity.

Comments are closed.