We Are What We Eat: Southern Cooking as Cultural Memory

An installment in our Appalachian Foodways series

Chef Jacques Pépin said that our food reflects our history. Around here, that’s not theory—it’s fact. Southern cooking isn’t just something passed down. It’s something that kept folks alive. It remembers what people went through, and it doesn’t let much go to waste. If you want to know who someone is, ask what they put on their table when the cupboards are getting low.

You could say this is the Southern version of “we are what we eat,” but in these mountains, it goes a little further. We are what we hold onto. What we put up for later. What we make when times are lean.

From Root Cellar to Recipe Card

Nobody in Southern Appalachia set out to style a cuisine. They just tried to get through the year without going hungry.

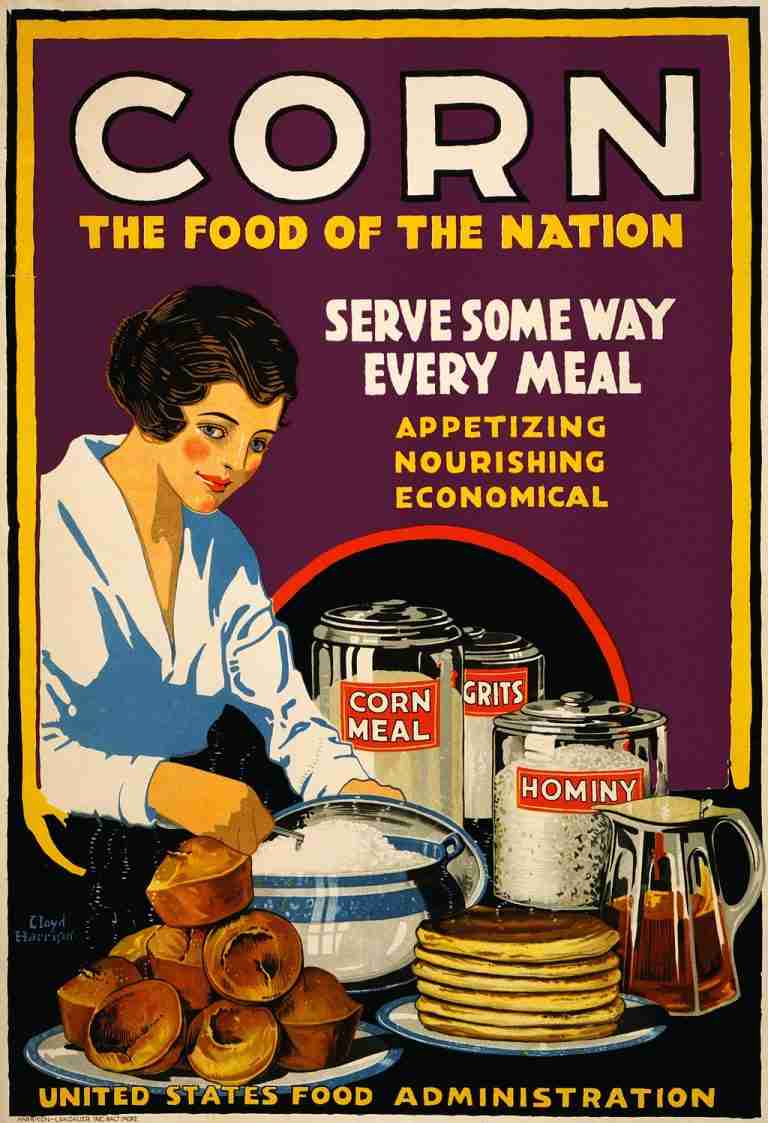

The garden, the henhouse, the smokehouse—those were the grocery stores. Cornmeal was the backbone of a hundred meals. Dried beans stretched across the week. Wild greens showed up in the spring, just when you’d had about all the potatoes you could take.

Food had to do more than taste good. It had to last. A ham bone flavored three pots. Biscuit dough showed up in tomorrow’s dumplings. If you had a sack of apples, you dried some and fried the rest. The goal wasn’t variety—it was survival.

These weren’t fancy meals, but folks kept making them even when they didn’t have to anymore. That tells you something.

The Blended Influences Behind Southern Cooking

Long before outsiders gave Southern food its name, it was already layered with influence.

The Cherokee had it figured out first. Corn, beans, and squash fed entire villages. So did chestnuts and ramps, before blight and development changed the landscape. Much of what later generations called “wild food” was just what the Cherokee called dinner.

African Americans brought okra and a deep knowledge of cooking over open flame—transforming what little was allowed into something richly flavored and sustaining. They carried entire traditions into a region that didn’t always remember to give credit.

And the Scots-Irish? They brought their love of buttermilk, pork, and cooking things low and slow in heavy pots. That cast-iron skillet in every Appalachian kitchen didn’t just show up—it traveled.

No single culture shaped this food. It came together over time, shared out of necessity, remembered out of love.

The Table as Witness

In the mountains, food often said what people couldn’t. It welcomed new babies, marked losses, mended fences, and made holidays feel like something worth waiting for.

People didn’t always write down what went into a recipe. They showed you. You watched the way a hand moved through flour. You listened for the change in sound when a pot of beans started to soften. If you asked how long to cook it, the answer might be, “Until it’s ready.”

The kitchen wasn’t a performance space. It was where the quiet work happened. And if someone stopped by around dinnertime, you added another plate and poured more tea. It wasn’t something to plan. It was just what you did.

Put It Up, or Do Without

Preserving food meant more than filling jars. It meant thinking ahead, being ready, not wasting what the garden gave. That kind of work taught a mindset.

Canning took time. So did drying apples on bedsheets, pickling beets, or stringing beans to hang from the porch rafters. But it gave families a kind of comfort. You could look at a shelf of jars in October and know you’d make it to spring.

Even now, you’ll find homes with pantries that lean toward practical. People still put up salsa, relish, jelly, chow chow—maybe not because they have to, but because someone showed them how.

And there’s something grounding in the rhythm of it. The same smell in the kitchen every summer. The same recipe, made from memory. You don’t always think of it as history—but that’s what it is.

What’s Changed, What Hasn’t

Sure, a lot of things are different. You can buy most anything now. Restaurants serve grits with truffle oil. Ramps show up on fancy menus, plated like treasures. Paula Deen and Edna Lewis have taken Southern cooking mainstream.

But even with the modern twists, the core remains. A pot of beans still tastes like home. Biscuits still get made in mixing bowls passed down two generations. Plenty of young cooks—some in cities, some on farms—are looking back on purpose. Not because it’s trendy, but because those old ways feel more honest.

Some are saving seed varieties their grandparents grew. Others are reviving community dinners or revamping family cookbooks. They aren’t just cooking food—they’re keeping something alive.

Why Southern Cooking Still Tells the Truth

When Pépin said food reflects our history, he meant the long arc of a people’s story. But in Southern Appalachia, the reflection comes close. You see the hardships. You see the neighborliness. You see how a place where life was never easy somehow became a place where people fed one another well.

Cast-iron skillets aren’t sentimental. They’re tools that earned their keep. Mason jars don’t just hold peaches—they hold summers. And cornbread isn’t just cornbread. It’s what you make when the power’s out, the rain won’t quit, and you still want something warm on the table.

So yes, we are what we eat. But around here, that also means:

We’re what we make room for.

We’re what we keep from spoiling.

We’re what we learned by standing beside someone who didn’t need a recipe card.

And when it’s all said and done, you can still learn a lot about this place by asking,

“What’s for supper?”

More Foodways Stories

Explore the dishes, tools, and kitchen traditions that shaped mountain life on the Foodways page.

Appalachian Foodways Collection

Enjoying Blue Ridge Tales? I hope so. If you’d like to help keep the site ad-free and the stories rolling, you can buy me a coffee.

To stay connected, subscribe to my Blue Ridge Tales newsletter, and have stories and updates delivered once a month to your inbox.